What is demand management? Is it a chimæra—a single entity that embodies two separate entities? Is it a selkie—a beast that has one form while in the water and another while on dry land? Or is it a sphinx—a monstrous combination of two disciplines, one that challenges us with its riddles?

Looking at the usage of the terms “demand” and “demand management”, both in service provider organizations and in management frameworks, these terms apparently refer to some very different concepts and practices. Sometimes they refer to the management of individual requests by consumers. In such cases, demand management reacts to the expression of demands and performs a front end role in a Demand to Value value stream. Other times they refer to an aggregation of demands by consumers. In this context, demand management concerns attempts to align demand and the capacity to fulfill it.

Although these two types of practices overlap, they each interface, in turn, with distinct sets of other practices. They require different skills to perform. They use different tools. We measure them in different ways. Thus, in spite of the homonymous terminology, the two practices are both real and distinct—not a question of “semantics”.

A different way of highlighting the diverse views of demand management would be to look at the sorts of questions they attempt to answer. One question is, “How shall we best handle the various requests made to us by our customers?” Underneath this question are various sub-questions: “From whom should we accept requests?” “How should those requests be normalized?” “What channel should be used to respond to a request?” “Should we attempt to fulfill the request and why?” “If so, when might we fulfill that request?”

A very different question would be “What should be done on the demand side about the imbalance between what our customers ask of us and our capacity to respond?” In other words, doing work is all about what happens when demand meets supply. Much of work management is about adjusting the supply side to align with demand. But we can also ask, “Given our imperfect alignment of our production capacity with the changing demands made on it, what can we do to influence or shape that demand to improve that alignment?”

In this article I will review the distinctive features of these two practices with a view toward disambiguating the terminology. I will look at the many different activities that various organizations consider as part of demand management. I will also look at how certain management frameworks consider demand management (if they consider it at all). As a side note, I would point out that some people might speak of “demand” and “managing demand”, but they really mean “managing supply (to meet that demand)”. While this issue is of fundamental importance for doing any type of work, managing supply is a very different, albeit closely related, discipline to managing demand.

Overview of Demand Management Activities

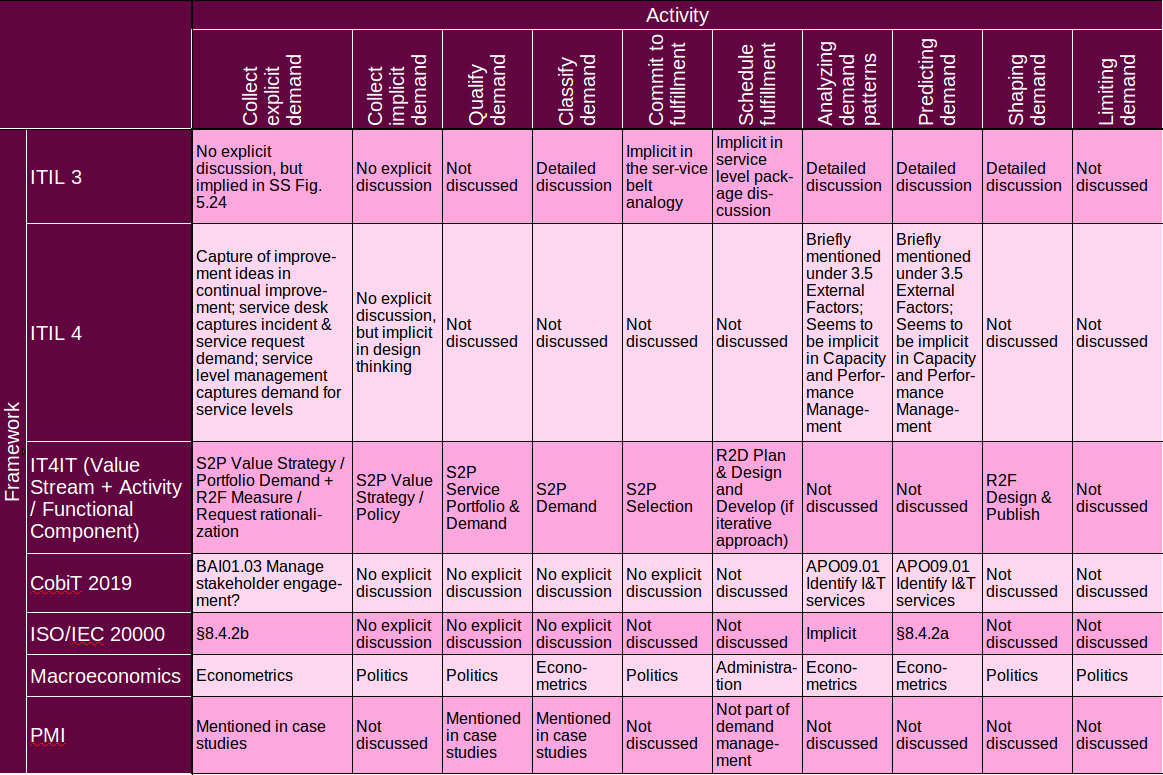

In this section, I will summarize the different activities of demand management, according to different frameworks and or in practice in various organizations. This will be a simple list, with no attempt to rationalize or justify the activities. Most organizations or frameworks consider demand management to include only a small subset of those activities.

Collect explicit demand from stakeholders

Consumers make explicit demands to their service providers. They have needs and they express them. They want new services. They want changes to existing services, both in terms of their utility and their warranty. They want to use the services on offer.

Consumers provide other types of input to service providers not generally considered as “demand” and not within the scope of demand management. Thus, consumers complain about services. Occasionally, they compliment service providers. They negotiate contracts and other agreements. They indicate failures and defects, with the expectation that the provide will remedy them.

These various types of explicit demand need to be collected and recorded. Subsequently, the service provider uses this information as the basis for many of its activities. Note that the service provide might reject or redirect a demand out of the scope of its mission.

Collect implicit demand

Consumers of services often do not express explicitly their wants and needs. The service provide must nonetheless be aware of them or, at least, be aware of what it supposes those wants and needs to be.

Why are consumers not explicit? Sometimes, they feel that the need is too obvious to articulate. Other times, the need is latent. As it has hitherto not been fulfilled, it is not consciously in any list of needs that the consumer might prepare. And sometimes, the service offering is so innovative that consumers have not yet realized how they might benefit from it. It can be a short hop from never having imagined using a service to feeling that that service is essential to your activities.

So, the service provider should collect “demand” that consumers have not yet articulated.

Qualify demand

- The waterfall approach: make sure you understand what the consumer wants before doing anything else or, at least, make sure that all the forms are filled in and the responsible people have signed them

- The agile approach: assuming that the nature of demand is always imprecise and changing, and that consumers are more apt to validate a service being delivered than to specify what ought to be delivered, the service provider institutes an iterative approach with fast feedback to narrow in on what the consumer really wants or needs

- The hubris approach: the service provider does what suits it best, whether consumers share that vision and can make use of the service, or not.

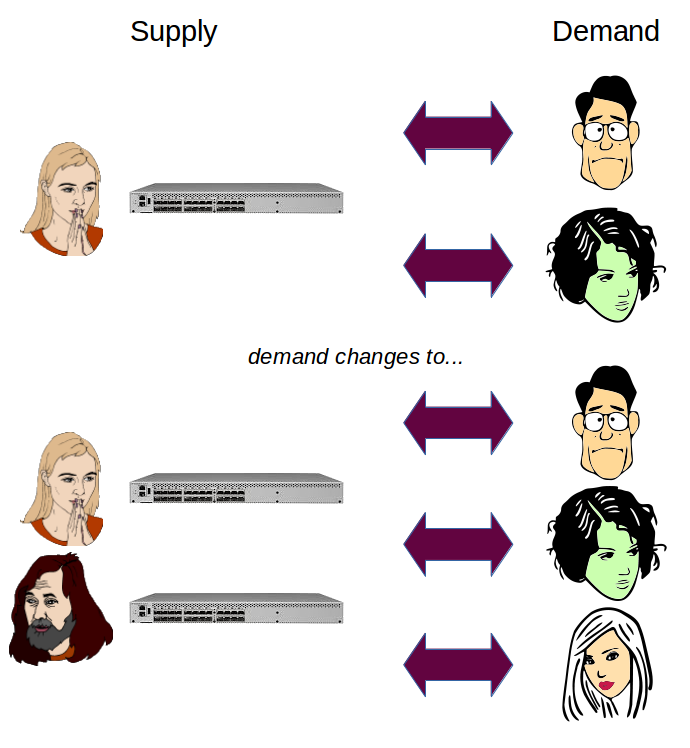

Classify demand

An important issue in most organizations is the imbalance, often temporary, between the volume of consumer demand and the volume of the provider’s ability to fulfill that demand. Providers apply many strategies to address this imbalance, most of which depend on the classification of demand.

Among the various types of classification is the prioritization of demand. This classification may lead to the decision to fulfill a demand, reject a demand or delay the decision. Such classification might assess the conformity of a demand to the vision and the strategies of the organization. Or, it might attempt to create a balance among the various service consumers.

Other classifications relate a demand to some broader context. In project-oriented organizations, demand managers might assign a specific demand, once qualified, to an existing project. Or, that demand might trigger a new project. In flow oriented organizations, the classification might assign each demand to a particular value stream.1

The purported value of fulfilling a demand might be the basis of classification. At the same time, the service provider might be classify its levels of risk. In other words, what is the probability that the provide can fulfill the demand and that the fulfillment will realize the desired value?

In flow-oriented organizations, demand management might classify the qualified demand according to its class of service. Thus, when a customer submits the demand to the input queue of the relevant value stream, the class of service provides the workers in that value stream with a criterion to decide when to start the fulfillment of the demand.

Some organizations include as part of demand management the assessment of the resources required to fulfill the demand. They use this classification, in turn, to schedule fulfillment or even to decide whether to fulfill that demand.

Commitment to fulfilling the demand

Demand management often ends with a gateway that formalizes the decision on whether to handle the demand. In general, the provider can commit to handling the demand; can reject the demand outright; or can defer a decision to some future time. The criteria are generally the same as used in the classification model.

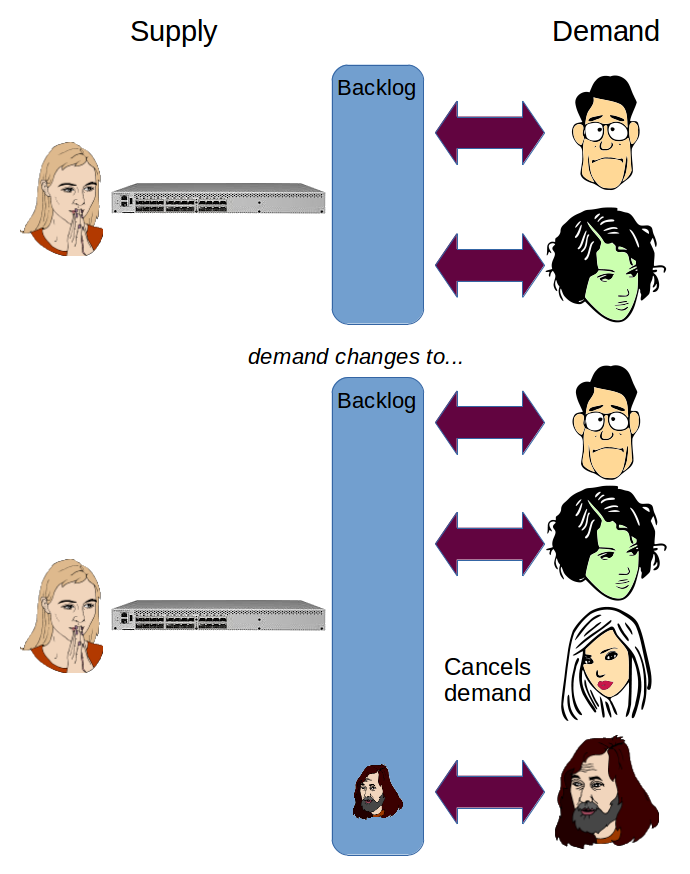

Some organizations take into account their capacity to fulfill the demand within a certain planning horizon. Rather than maintain a demand indefinitely in a backlog, the provider will reject the demand if it does not have the capacity to fulfill the demand within the planning horizon. They assume that circumstances are likely to change while the demand idles in a backlog, often making the demand less relevant to the requester’s needs. However, if the demand nonetheless remains important for the customer, it will reactivate that demand in the future.

I distinguish between the notion of a commitment gateway and the question of whether the demand falls within the scope of the provider’s mission or its capabilities. Customers sometimes misdirect demand. In such cases, the provider might reply, “We don’t do that type of work” and politely redirect the demand to a different supplier.

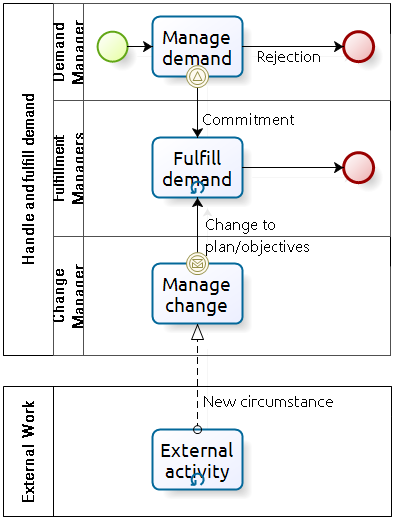

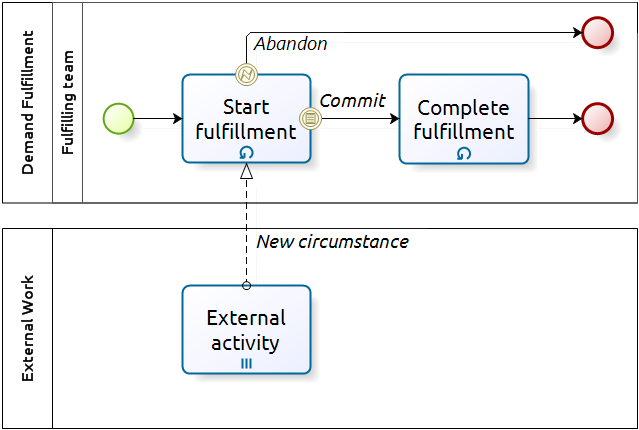

The waterfall approach to handling demand (see Fig. 5) believes that the commitment decision should be made as early as possible. According to this belief, early rejection prevents the wasteful use of resources handling demand that will ultimately remain unfulfilled.

However, this approach ignores the value of open options. By keeping options open and delaying commitment (see Fig. 6), the provider remains more agile. In such cases, especially when an organization does its work in a flow-oriented manner, commitment is often not part of demand management at all. Such organizations delay the commitment to performing work, as well as the possibility of rejecting work, into the fulfilling value stream.

Scheduling fulfillment

Some organizations plan fulfillment as part of demand management, after having qualified, classified and accepted that demand. However, other organizations have roles separate from demand management to plan and schedule fulfillment. Indeed, flow-oriented organizations do not perform generalized planning, per se. They perform their work according to the appropriate value stream phases and when good flow of work permits it. The team performing the team plans internally how it will execute the necessary tasks.

Analyzing demand patterns

The analysis of demand patterns answers three questions: Who are the customers? What do they want? When do they want it? The answers to these questions are useful for designing and evolving the services delivered to these consumers. Providers may use them, too, as input to two other demand management activities: predicting demand and shaping demand.

The level of demand for a service differs from the level of fulfillment of that demand. If that fulfillment does not equal 100% of the demand, the reasons are often not due to demand management issues, as illustrated in Fig. 7. Therefore, analysis should recognize that the fulfillment level is only a proxy for the demand level.

Insofar as the service provider competes in a marketplace, the provider may take into account demand relative to the broader market’s demand in addition to existing demand from its own customers. Such pattern analyses might identify the impact on services when competitors change prices or offer new forms of utility and warranty.

Demand may concern the use by existing consumers of production services, just as it may concern the needs and wants of potential consumers for new services or changes to services. Understanding the drivers for these different types of demand might require very different techniques. For example, many services are have daily, weekly or seasonal cycles for demand. There might be considerable consistency from day to day, week to week or year to year in the patterns of service demand. However, the patterns for demands to change those services might have no discernible cycles or those cycles might be quite different.

Predicting demand

Demand prediction uses as input the analysis of demand patterns to predict, plan and budget the impact of changing demand on the provider’s resources. One the one hand, insofar as services generate revenue, predicting demand is a key input to budgeting for future, expected revenue. On the other hand, demand predictions may influence the allocation of production resources.

The various provisos I have described for the analysis of demand have an impact on the prediction of demand. For example, a simple (if unsophisticated) way of predicting the demand for service actions is to make linear extrapolations from the identified patterns. Predictions of stochastic demand might use Monte Carlo simulations.

Such methods are commonly used to predict the demand for service acts for existing services. However, it may be extremely difficult to extrapolate from past demand for new services or service changes to predict future demand for new services or service changes. But, in all cases that I have ever seen, such demand always outstrips the supply.

Matching supply and demand

Strictly speaking, the work of matching supply to demand is not really a demand management activity. Providers are often prejudiced in favor of resolving the imbalance between supply and demand by acting on the supply side. The desire to take an ever larger share of the market drives this prejudice. Providers are optimistic that this can be achieved, if only it could manage supply well.

A systematic approach, treating supply and demand interdependently, might be a more reasonable way to achieve a desirable balance. Be that as it may, most organizations have well developed supply management and less well developed demand management. So I will continue to treat supply and demand management as different disciplines.

Service providers use the output of the demand prediction activity to plan the levels of the supply side resources. Thus, the needs of matching strongly influence the sorts of information that demand prediction ought to provide. Furthermore, understanding the possible strategies for matching supply and demand sets the stage for the following activity, shaping demand.

There are fundamentally five approaches to matching supply and demand:

- Dynamically adjust the production resource levels to match the predicted demand. Currently, two types of resources are sufficiently elastic to apply this strategy: the people performing services and the virtual computing assets created and rented on demand from third party suppliers (i.e., from the cloud). Employing people only on demand is socially unacceptable in many contexts. However, highly automated service delivery can well benefit from computing power on demand.

- Keep the production resources level and absorb the differences with demand via changes in inventory, in order backlog and in lost sales. This is inefficient and is likely to cause customer dissatisfaction. And yet, providers commonly use this approach.

- Only produce output following a firm demand. While this approach is efficient and reduces much risk, it does not address the issue of evolving aggregate demand or changes to desired service levels. This strategy applies only to goods.

- Limit the allowable volume of demand. Rather than putting unfulfilled demand in a backlog, the provider prevents the demand from being recognized. I describe this strategy below.

- Influencing or shaping the demand. Using various techniques, such as pricing and demand prioritization, the service provider can attempt to adjust the demand to better match the available supply. When manufacturing goods, for example, a provider can attempt to reduce excess inventory by lowering prices. Service providers do not have such problems as there cannot be a surplus inventory of service output. There can, however, be unproductive assets.

Most organizations will combine two or more of these strategies.

One might wonder if it makes sense to treat demand-side management and supply-side management as separate disciplines, given the close and interdependent relationship between them. I will leave that question for a separate inquiry.

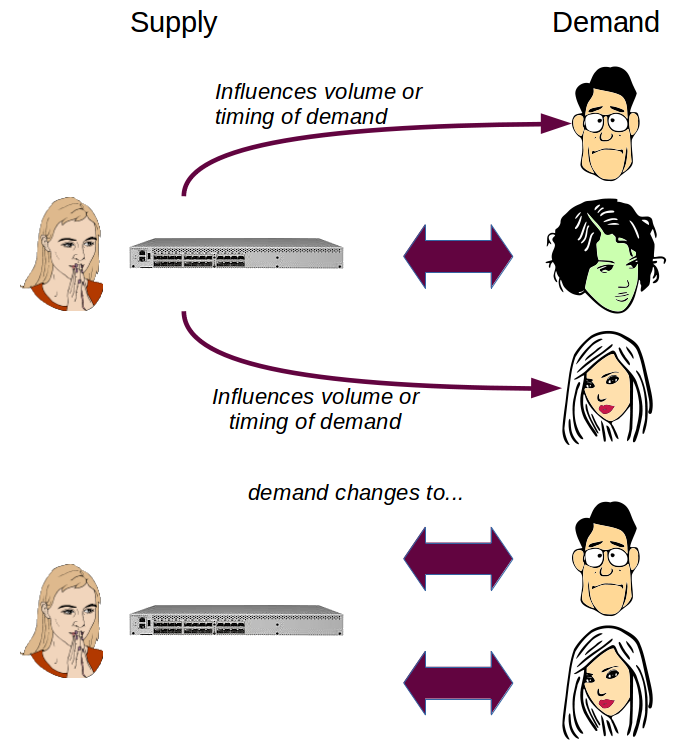

Shaping demand

A service provider may decide to dimension the assets used to deliver services based on a certain peak demand and level of service. As a result, it will under-utilize those assets during periods of off-peak demand. Since the investment in those assets, whether used or not, is generally very similar2 the provider may prefer to use the assets at a higher level, even if the per service revenue is lower. To achieve this end, the provider needs to attempt to shape the demand for services.

Shaping demand may take many forms. Here are some examples:

- offering different service levels to match different customer profiles, on the assumption that some service levels require more assets than others

- adjusting prices, either temporarily or according to the patterns of use, so as to encourage greater demand during off-peak periods

- packaging together multiple services, which results in changed patterns of consumer activity, often intended to increase demand.

Limiting demand

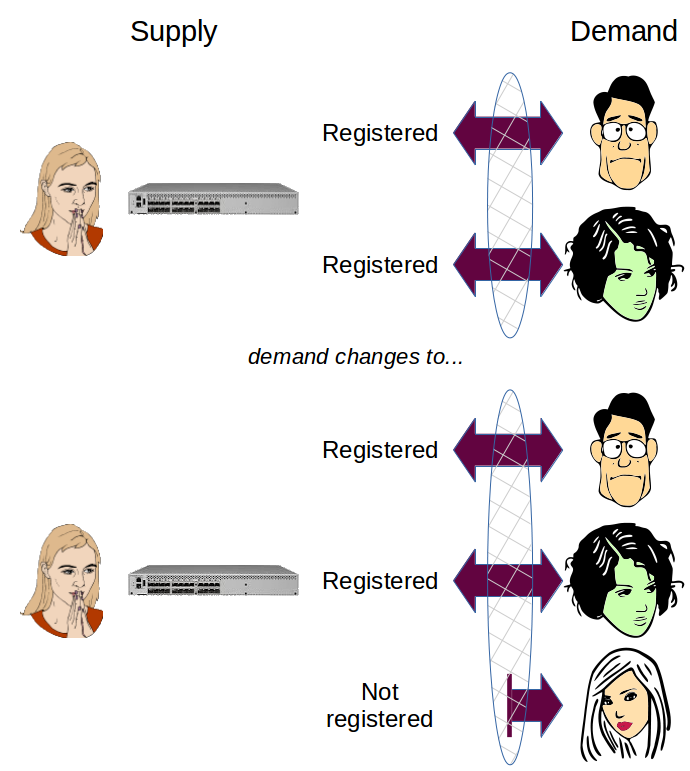

A service provider can limit demand by organizational means, technical means and procedural means.

Service providers implement organizational limits to demand by authorizing only certain customer roles to submit demands. Such roles also allow the provider to offload some of the qualification and classification duties to the authorized submitter. Providers may implement this approach both for internal customers and in a business to business context, with formalized agreements for handling demand.

Capturing demand input from customers via software provides a technical means for limiting demand. The provider can turn on or off the option to register new demand depending on provider policies, such as the acceptable size of the input queue for demand. This approach might dissatisfy customers thereby lacking the means to express their needs. The provider assumes, however, that any need of sufficient importance will last until it re-enables function to capture new demand.

A flow-oriented organization may use procedural means for limiting demand. As with a technical approach, such organizations might limit the size of the input queue or might limit the number of open demands that a given customer might submit. In some cases, the provider will leave to the customers the responsibility to prioritize their own backlogs of demand, limiting only the number of demands it accepts in its input queue. In other cases, the provider will define a procedure to receive demand. A typical example would be a simple round-robin procedure where the right to submit a demand passes from customer to customer, in a continuous cycle. This approach allows customers to maintain control over the priorities of demands, while limiting the work in progress.

Demand Management Issues

In the following section I will discuss various issues central to an understanding of the nature of demand management and its scope. In particular, I will look at:

- How demand management relates to service request management

- The distinction between managing detailed demand for change and aggregated demand for services

- The leveling of demand and supply

Managing Demand and Service Requests

In the generic sense of the term “demand”, service requests are obviously a form of demand. So are requests to resolve incidents, for that matter. Many organizations treat demand management and service request management as distinct disciplines. Is service request management nonetheless a subset of demand management? A useful way to answer this question is by comparing the purposes and the practices of these disciplines.

The assessment in Fig. 12 indicates that the activities of service request management are a proper subset of the activities of demand management. Furthermore, consider that neither demand management and nor service request management deliver output directly to service consumers. Both hand off their tasks to other practices for ultimate fulfillment.

The comparison of service request management to demand management highlights an important distinction in how we conceive of the latter. The former, especially if one considers that it handles only predefined requests (not a universal definition), is highly susceptible to automation. Demand management, in contrast, may be split between the types of demands that are also automated (the demand for core IT services) and the types that (still) require considerable manual handling (the demand for new services or for changes in services). Furthermore, actions that are automated are generally uniform, in spite of a set of execution options. For example, when a user requests a password reset, a given organization will almost always perform that reset in the same way. Similarly, when an accountant posts a journal to a general ledger, the software executes the posting in a consistent, algorithmic way.

On the other hand, service providers handle requests for a new service with a great deal of variation, even if the broad outlines of the value stream remain consistent. New service request handling tends to be complicated, if not complex. Service request handling tends to be obvious, although some might be a bit complicated.

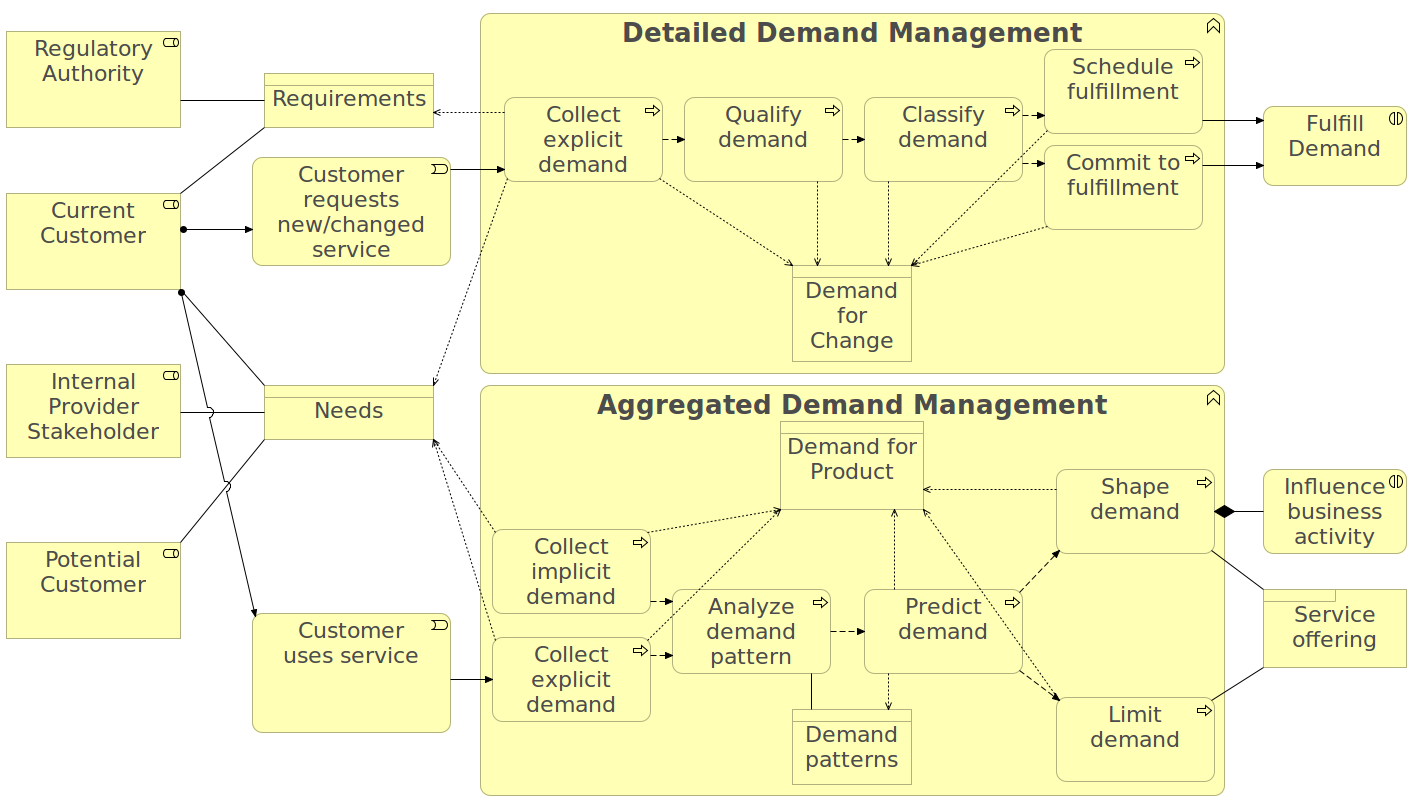

Managing detailed demand and aggregated demand

I described above how demand may be distinguished according to the degree to which it may be handled in a consistent and even an automatic way. Whether organizations handle demand on a case by case basis or in the aggregate distinguishes very different understandings of the discipline. The various management frameworks, too, show this distinction in their conception of demand management. It helps to understand the mutual incomprehensibility that often occurs when two people from different management backgrounds talk about demand and demand management (see Fig. 14).

Management of detailed demand

Many frameworks and many provider organizations consider that demand management handles individual demands. It passes those demands through some form of pipeline, process or value stream, handing off its output to some other discipline for further treatment. Detailed demand management answer questions like, “Our customer wants x; should we fulfill that presumed need?”

Although frameworks such as project portfolio management basically concern the handling of individual demands to be fulfilled via projects, they also have a notion of aggregation—the project portfolio itself and the resources available. However, the portfolio aggregates projects and the resources they require, not demands. When an organization rejects a demand, it does so on the merits of the individual demand relative to other demands. In other words, project portfolio management aggregates on the supply side but handles the demand side case by case.

When managing detailed demand, the dominant activities are:

- Collecting explicit demand

- Collecting implicit demand

- Qualifying demand

- Classifying demand

- Committing to fulfillment

The output from detailed demand management generally goes to such disciplines as:

- Project Portfolio Management

- Project Management

- Service Design

- Change Management

depending on the architecture of the organization’s processes.

Management of aggregated demand

In other organizations, demand management concerns demands in the aggregate rather than demands handled on a case by case basis. Handling the details of demands is left to other disciplines, such as service request management, requirements management or executing the service actions.

For such organizations, the management of detailed demand is either a purely operational issue—such as fulfilling the demand for a core service—or a design issue—such as in deciding whether to assign a given demand to a given project. They do not consider individual demand handling as a strategic activity, although it depends on applying previously defined strategies. Aggregated demand management answers questions like, “Our customers have a certain level of demand; how should we economically balance that level with our resources?”

The dominant activities in the management of aggregated demand are:

- Collecting explicit demand

- Qualifying demand

- Classifying demand

- Analyzing demand patterns

- Predicting demand

- Shaping demand

- Limiting demand

The management of aggregated demand is mostly a strategic or design activity, although more agile organizations may take it into account during operations. It answers these sorts of questions: “What strategies should we apply to better balance supply and demand, reducing our costs while continuing to satisfy our customers?” or “Given that we expect a certain evolution in the demand for this service, how should we design that service to easily adapt to the changing demand, while keeping costs reasonable and maintaining the performance our customers expect?” At an operational level, it answers questions like “We are experiencing a surge in demand right now; how shall we handle it to maintain the continuity of our service levels?”

The output of aggregated demand management generally goes to such disciplines as:

- Business modeling

- Business relationship management

- Service level management

- Capacity management

- Financial management

- Service design

Demand and Supply Leveling

I described above the strategies typically used for balancing what a company produces with what its consumers buy. Demand management is one of these strategies.

The approaches to demand and supply leveling for services are similar to the leveling for goods. The first exception concerns the production of output following a firm demand. There can be no service act unless there is some firm demand for it. The second exception concerns the adjustment of inventory. Service output, which is always received directly by the consumer, does not enter an inventory. Furthermore, deliberately increasing the inventory of unfinished services procures little benefit. In almost all cases, the consumer prefers to receive the service output sooner rather than later. On the other hand, both the production of goods and the production of services face the issue of having invested in production resources, whether they are used to produce goods or services—or not.

How frameworks use "demand" and "demand management"

Here is a brief review of how various frameworks describe “demand” and “demand management”. My choice is based on the desire to illustrate some of the main streams of thought. Therefore, I consider demand management from a macroeconomic point of view, as well as from an IT architecture, a service management, a project management and a general business management perspective.

Most of the frameworks’ conceptions of demand management have evolved through their various versions. I ignore the older versions as being less used today. For service management, I ignore ITIL® 1 and ITIL 2. ITIL 3 (and 2011) have important differences with ITIL 4. ISO/IEC 20000, too, has evolved, sometimes lagging behind and sometimes leading ITIL. I consider only the latest versions of CobiT® and PMBOK®. As for macroeconomics, my goal is not to review how theory has evolved over the past 90 years, but rather to indicate some underpinning trends that ultimately influence the service management discipline.

I provide a summary of what these frameworks say in Fig. 15. First, an explanatory note about that table. It distinguishes between “no explicit discussion” and “not discussed”. In the latter case, the activity is simply not present in the framework and there is no reason to believe that it is somehow hiding behind the wording. In the former case, the activity is not mentioned in so many words, but one infers that somehow the framework is making an elliptical reference to the activity.

ITIL 3

ITIL 3 calls demand management “a critical aspect of service management”. It considers demand management mostly in the aggregate. It discusses demand management as part of service strategy, not as part of service operations. Its techniques include off-peak pricing, volume discounts and differentiated service levels. Patterns of business activity, which are related to user profiles, drive demand. It drives, in turn, differentiated service offerings and service level packages.

ITIL 3 defines demand management as:

Activities that understand and influence Customer demand for Services and the provision of Capacity to meet these demands.

ITIL provides no explicit explanation of the scope of “demand”. However, the discussion of service request management in the Service Operations book makes clear, on the one hand, that service requests are a subset of demands. Confusingly, ITIL 3’s discussion of demand management makes it clear, on the other hand, that this practice complements service request management. The former concerns handling, in the aggregate, the demand for services, whereas the latter is concerned with handling, in detail, the demand for services that support the provider’s core services.

The remaining types of demand concern the various services offered by the provider.

ITIL 4

Demand Management

ITIL 4 has not defined a specialized demand management practice as of this writing. Thus, demand management goes from a “critical aspect of service management” in ITIL 3 to a vague concept, at least as per the ITIL 4 Foundation. I don’t know if this omission is an oversight or is deliberate.

ITIL 4 defines “demand” as:

Input to the service value system based on opportunities and needs from internal and external stakeholders

This definition does not distinguish between the individual demand and the aggregate of demands. Unfortunately, that definition does not really tell us what demand is. While demand is clearly a type of input to the service value system, are there any other types of input that are not demands? If so, how may they be distinguished from demand?

What does ITIL Foundation intend by the absence of any discussion of demand management, given its strategic importance in ITIL 3? I will not try the reader’s patience by speculating further, but provide some additional notes below.3

Service Request Management

ITIL 4 makes a significant break with ITIL 3 regarding the definition of service requests (although one might ask is this break is intended). It defines a service request as:

A request from a user or a user’s authorized representative that initiates a service action which has been agreed as a normal part of service delivery.

It defines a service action as:

Any action required to deliver a service output to a user. Service actions may be performed by a service provider resource, by service users, or jointly.

These definitions make no distinction between core and supporting services. Thus, if a service provider offers an email service, the service actions are the various steps of receiving messages from a user’s client and delivering those messages to the recipients’ relevant mail transfer agents. And, vice versa, to receive that incoming mail and deliver it to the recipients’ mailboxes.

What initiates those actions? It is obviously the clicking on the Send button in the sender’s email client. Thus, according to definitions in ITIL 4, clicking on that button is an example of a service request.

Unfortunately, this concept appears to contradict the key message of ITIL 4 about service request management:

The purpose of the service request management practice is to support the agreed quality of a service by handling all pre-defined, user-initiated service requests in an effective and user-friendly manner.

The key phrase in that message is “to support the agreed quality of a service”. There appears, then, to be a distinction between delivering a service and supporting the quality of that service. Indeed, ITIL Foundation (p. 156) provides a list of various types of service requests, in which the delivery of core services is not included. I conclude that the glossary definition of service request is far too general and would benefit from greater precision.

Which practice, according to ITIL 4, handles requests from users that are not pre-defined? Is there some discipline intended to handle such requests? Could that discipline be demand management? It is an enigma.

IT4IT™ 2.1

IT4IT does not discuss demand management, per se. Rather, it provides a framework within which we may position the activities of demand management. It briefly mentions demand management in the context of a KPI for the Strategy to Portfolio value stream:

Demand requests, types, and delivery per service % of overall IT budget that can be traced to formalized demand requests. Structured and rationalized Demand Management with ongoing efforts to minimize the number of demand queues that staff must respond to.

Thus, IT4IT recognizes demand management as a discipline having certain management goals. That being said, the above statement sounds suspiciously like supply management rather than demand management.

IT4IT describes the work of IT as a value chain composed of four value streams. I would split the handling and management of demand among three of those value streams:

- Strategy to Portfolio

- Requirements to Deploy

- Request to Fulfill

I hypothesize that IT4IT considers requests to resolve incidents, which are part of the Detect to Correct value stream, to be distinct from the sorts of demands typically handled by demand management.

The principal value stream for handling demand to add or change services would be Strategy to Portfolio, especially the demand activity, which includes:

- Consolidate demand

- Analyze priority, urgency, and impact

- Create new or tag existing demand.

The value stream for handling the demand to perform service acts would be Request to Fulfill. IT4IT defines several functional components in this value stream that might relate to demand management: the Engagement Experience portal, the Offer Management component and the Offer Consumption component. They have the potential to influence and shape consumer demand for services. However, those functional criteria are not mentioned by IT4IT for any of these components.

I will continue my analysis by describing how various functional components of IT4IT may embody demand management activities.

Demand Management

IT4IT has no functional component called “demand management”.4 It mentions the term once, as quoted above, but does not further describe demand management’s purpose, functions or metrics.

I have talked about the contrast between management of demand in the aggregate versus the management of individual demands. The value chain orientation of IT4IT lends it to better understand the handling of individual demands than aggregated demand. Although management of demand in the aggregate is possible within the IT4IT context, the framework does not flesh them out very well (see below).

I continue now illustrating how various functional components

Policy Functional Component

When does the service provider define demand shaping and how is it related to policies? Techniques for shaping the demand for services should be far upstream in the value chain, well before the provider collects any explicit customer requirements. I would place the shaping of demand in the Strategy to Portfolio value stream, well before the Requirement to Fulfill value stream. Demand shaping would be the result of some strategy, expressed in a policy. Its techniques would be defined as part of a conceptual service or a conceptual service blueprint.

Differential pricing is one of the techniques used to shape demand. According to IT4IT, a service provider “Shall define pricing/costing Policies and capture information related to Service Contracts”. Although IT4IT describes an IT Cost Model artifact, it makes no mention of a pricing model artifact.

We may perhaps assume that other demand shaping techniques, such as service packaging or service level packaging, may be the result of policies, although IT4IT does not explicitly mention them. The Service Level Functional Component, described in the context of the Request to Fulfill value stream, concerns itself with individual service contracts rather than the strategy of service level packaging. Thus, if service level packaging is used as a demand management technique, it most likely would have its initial expression in the conceptual service. However, it may be refined and tuned as part of the Offer Management component and the catalog composition function component.

Portfolio Demand Functional Component

The Portfolio Demand Functional Component is part of the IT4IT’s Strategy to Portfolio value stream. This component handles, via a variety of channels, all the various types of demands that customers might make to a service provider. Thus, demand includes such items as requests for new projects, requests for fulfillment of support services, requests for the resolution of incidents, requests to make improvements, etc.

Portfolio Demand assesses and prioritizes demand, which it hands off to the Requirement to Deploy value stream.

Request Rationalization Functional Component

One of the purposes of this functional component is to “enable the recording of patterns of service consumption that can be used to shape demand for new and/or improved services”. This component accounts for the capture of the use of services, which relates in part to the demand for those services. To which other functional component, in which demand is presumably shaped, does it provide such reports of patterns? The level 2 model (Figure 61 in IT4IT) does not provide a clear answer.

Catalog Composition Functional Component

The Request to Fulfill value stream also has a Catalog Composition Functional Component that creates Service Catalog Entries. These entries include the pricing for the service. Is it IT4IT’s intention to say that service pricing is only determined at this (late) point in the value chain?

This makes sense for the cases where pricing is adjusted to reflect temporary or evolving conditions. Thus, a service might be “on sale” during the slow summer months. A new competitor with a low price might require changes to keep market share. Or, when a pricing model is based on costs and those costs change significantly, the price, too, might need to be adapted.

However, one might expect that pricing strategy is part and parcel of the concept of a service. A service concept should describe the targeted marketplace niche. That niche is often characterized by the targeted price range. In such cases, the pricing is tightly constrained by the strategic decisions (policies?) determined during the Strategy to Portfolio value stream. But IT4IT does not instantiate this hypothesis.

In sum, there is a lot of guessing involved in placing demand management activities among the various functional components of the value chain. I wonder if fully worked out examples might result in some changes to how those functions are defined.

CobiT 2019

Obtain a common understanding between IT and the other business functions on the potential opportunities for IT to enable and contribute to enterprise strategy.Furthermore, EDM02.02 Evaluate value optimization is described as:

Continually evaluate the portfolio of I&T-enabled investments, services and assets to determine the likelihood of achieving enterprise objectives and delivering value. Identify and evaluate any changes in direction to management that will optimize value creation.While these activities do not explicitly refer to influencing customer demand, they do speak of influencing customer strategy which, if implemented, should also influence demand. In sum, although CobiT does not recognize demand management as a discipline with distinct goals, metrics, responsibilities and activities, demand management activities are implicit in other domains that CobiT does recognize. CobiT puts special emphasis on the alignment of IT with “the business” It inherits thereby a long-established view of IT as somehow distinct from “the business”, even if it does not explicitly share that view. Thus, CobiT does not include some of the classical techniques for influencing service demand, such as differential pricing. Whereas CobiT defines clearly the management and control of costs, it includes virtually no discussion of pricing, for which it mentions neither goals, responsibilities, controls nor metrics.

ISO/IEC 20000:2018

In its 2018 edition, demand management finally emerges as a distinct discipline in ISO/IEC 20000. Hitherto, it had been implicit in other disciplines, such as capacity management. Demand management in ISO/IEC 20000:2018 is a very limited, but well-aligned, subset of the concepts in ITIL 3. The standard takes the perspective of managing supply and demand, rather than developing service strategies.

Fundamentally, ISO/IEC 20000 limits its discussion of demand management to capturing current demand, predicting future demand and informing other disciplines, such as capacity management and financial management, of this information. Not only does the standard ignore the concept of shaping or influencing; it implies that it is the role of capacity management to meet the demand, rather than influencing demand to improve the management of capacity. Of course, the objective of the ISO/IEC standard is not to flesh out a complete service management system, but only to describe required or strongly recommended activities. This approach allows for a broader, non-mandatory view of demand management.

ISO/IEC 20000-2:2018 §8.4.2.2 explains that:

The purpose of this required activity [demand management] is to understand demand so that the organization [the service provider] can adjust capacity as needed to operate the SMS [the service management system] and [my emphasis] deliver services effectively.

I infer from this statement that the standard refers to the demand for core services [i.e., “deliver services effectively”] as well as the demand for support services such as service request or incident handling [i.e., the SMS].

Economics and Politics

Looking at the broader subject of economics, demand management has various meanings according to the context. One might usefully split its activities into econometrics (capturing, measuring and analyzing demand), politics (making decisions about the allocation of scarce resources) and administration (acting on those decisions).

Keynesian Macroeconomics

The pump priming by the U.S. government during the depression of the 1930s represents a classic example of demand management based on Keynesian economics. According to this concept, a government can try to stimulate economic demand and reinforce economic cycles in cases where other forces in the economy fail to do so. Thus, the government attempts to shape demand at the aggregate level by providing employment and injecting liquidity into the market.

When economic levels depend on economies of scale, such as in the production of solar electrical cells, government might temporarily accord tax incentives to stimulate demand that, in turn, is supposed to help bring down prices.

When economics is shaped by conservative policies, similar policies shade into the give-aways to rich constituents via subsidies and tax incentives, whether the benefits trickle down to others, or not.

Resource Management

Currently, certain economic actors are attempting to influence the demand for certain scarce resources, such as energy. Of course, other actors take a laissez faire attitude and reject the idea of intervening to change demand levels. Thus, private associations and certain government might promote the use of renewable energy sources, passive energy management, more efficient use of energy or even the reduction in energy needs through increased insulation and lowering of consumer expectations. Note that governments are also very active in supply management, typically providing subsidies to such sectors as agriculture and energy production.

Project Management

I combine in this section PMI® and PRINCE2® for the simple reason that neither has much to say about demand management. This, in spite of the fact that many organizations that have adopted one framework or the other also have a well defined demand management discipline.

It may be useful to consider project-related frameworks in terms of how they view events during and after the initiation of a project, as opposed to events before that initiation. While some form of handling the demand for work is implicit in the discussions of project initiation, there is relatively little explicit discussion of how to manage that demand as a discipline in its own right.

For PRINCE2, demand management is an activity upstream from project management and is therefore out of the scope of its advice. Other related frameworks, such as P3M3®, P3O® or even MoP® may have a little more to say about the subject. Be that as it may, that advice is fundamentally about alignment of provider strategy with customer strategy. It may also describe techniques for recording and assessing consumer demand that projects or programs might subsequently address.

The Project Management Institute’s lexicon does not include a definition of demand management. However, it has published some case studies which define demand management as:

…the process an organization puts in place to internally collect new ideas, projects, and needs during the creation of a portfolio.5

Given the context, that “portfolio” is a portfolio of programs, projects and related types of work. The authors recognize that demand management (in the context of project and program management) is often a reactive activity that simply “harvests” ideas and requests. They argue, however, that it should be more proactive. However, being proactive is, for them, not a question of influencing demand. Rather, it is a question of profitably analyzing and prioritizing demand.

Some organizations assign a broader scope to what they call demand management. It ranges from the reception of any input that might lead to a project, through the qualification and prioritization of that input. The output is the assignment of the input to a project or the rejection or postponement of that input. By “qualification” I mean the formalization and classification of the initial input. In the most extreme case I have seen, demand management also provides an assessment of the data required to schedule the project, including the resources required, the duration of the work and any dependencies on other types of work. The risk is that demand management becomes a project in and of itself that does much of the work that the subsequent project will redo.

CMMI-SVC 1.3

CMMI® for Services presents demand management within the context of capacity and availability management. Thus, it is strongly focused on the problem of balancing aggregated supply and demand. While it refers to the existence of demand management techniques to influence demand, it does not describe any of those techniques. Further, it states that although using such techniques may allow for more sophisticated management of demand and supply, demand management is not always possible.

CMMI-SVC considers service requests in a very broad way:

A communication from a customer or end user that one or more specific instances of service delivery are desired.

From the examples given, “instances of service delivery” could be a core service action, a service support action, or any other form of service delivery. Consequently, service requests are one manifestation of “demand”, which may be managed in terms of capacity and availability.

Conclusion

I have examined with a little detail the various activities that might constitute demand management. I have then examined how various management frameworks regard demand management. We have seen that demand management ranges from a fully articulated discipline, as in ITIL 3, to a phantom discipline, as in PRINCE2 or ITIL 4. Some frameworks emphasize managing demand on a case by cases basis, whereas others emphasize aggregated demand.

There are are examples of good definitions of “demand”. In most cases, the frameworks seem to assume that the meaning of the term is obvious, so no special definition is required. But this leads to considerable ambiguity regarding the scope of demand and demand management. Is a demand any customer event that leads to some effort by a provider? Does it include only certain types of events? I have used the example of service requests to examine how, on the one hand, service requests share the characteristics of other types of demand and yet, on the other hand, several frameworks treat service request management as a very different discipline from demand management. Is this really necessary? Could such frameworks be simplified?

If we were to consider projects and programs as services, then the logical distinction between the types of demand that I discuss above would disappear. But when considered in the practical terms of processes, process architecture, responsibilities and tools, demand management can be many different things.

I do not pretend that there are right and wrong understandings of demand management. However, I have hoped to show that organizations using only a very limited comprehension of this discipline might consider how much more they might achieve by expanding the practice.

So what is demand management? Is it a chimæra—a single process that embodies two separate processes? Or is it a selkie—a beast that has one form while in the watery grave of project management and another while on solid land of balancing supply and demand? Or is it a sphinx—a monstrous combination of two separate disciplines, one that continues to challenge us with its riddles?

![]() The article Demand Management: Chimæra, Selkie or Sphinx? by Robert S. Falkowitz, including all its contents, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

The article Demand Management: Chimæra, Selkie or Sphinx? by Robert S. Falkowitz, including all its contents, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Notes

3 Here are some additional notes about demand and, possibly, demand management, according to ITIL 4.

We are told that that input is “based on” opportunities. This is very hard to understand. Perhaps service offerings are based on opportunities, but that does not mean that there will be any demand for those offerings.

We are also told that that input is based on needs from stakeholders. What does this mean? Service designers are stakeholders of the service value system. They need to earn a living, get paid for their work. Is this a basis for demand? I don’t think so. Consumers are also stakeholders. They use the services being offered. Clearly this a the result of their demand for those services.

But what sort of demand? Are we talking about the request to offer a new service or to change an existing service? Are we talking about a request to perform an instance of a service, perform the service act? Both? Yet other meanings?

This definition is strong on provoking question; weak on answering them.

ITIL 4 also defines demand as follows:

Demand represents the need or desire for products and services from internal and external customers.

Once again the definition raises more questions than it answers. It seems to say that “demand” is a symbol or an abstraction of customers’ needs or desires. We may perhaps have to assume that those needs and desires are expressed. They do not remain latent. Thus, they are input in the service value system, input that triggers the service value chain.

The diagram of the service value system shows a double-headed arrow linking opportunities and demands to the rest of the system. This implies that the rest of the system can influence the demands, although this influence is not stated explicitly in the explication of the system.

When it comes to the management of demand, the closest ITIL 4 comes to this question is in the discussion of capacity and performance management, where it says:

An understanding of capacity and performance models

and patterns helps to forecast demand and to deal with incidents and defects.

Unfortunately, there is no discussion of such models, no example provided. Thus, it is mysterious to me how a capacity and performance model can be used to predict demand. It is one thing to say that an increase in demand is likely to result in a decrease in performance, all other things being equal. But that is not the same as implying that a decrease in performance will result in an increase in demand, which is the only way I can understand what ITIL 4 is saying. In mathematical terms (we are talking of models), it might be true that ƒ(demand) = performance, but this does not mean that ƒ(performance) = demand.

We may close this discussion of ITIL 4, pending the completion of the publication cycle, with a review of how the term “demand” is used in context. For example, ITIL Foundation describes the service desk practice as follows:

The purpose of the service desk practice is to capture demand for incident resolution and service requests.

I think it obvious that in such use we are talking about individual demands that trigger incident and service request handling (in spite of the fact that the service desk’s. purpose goes far beyond the mere “capture” of these demands).

On the other hand, other citations are clearly referring to demand in the aggregate:

However, for organizations bearing a legacy of old IT architectures and IT management practices focused on control and cost efficiency, the new business demand [i.e. shorter time to market] has introduced a greater challenge.

For example, the number of spare computers an organization requires can be calculated based on…demand predictions from capacity and performance management.

Credits

Unless otherwise indicated here, the diagrams are the work of the author.

Fig. 1: Downloaded from https://www.ranker.com/list/chimera-animals/mariel-loveland

Fig. 2: By Siegfried Rabanser – Seehundfrau in Mikladalur, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=68573408

Fig. 3: Detail by Gustave Moreau – This file was donated to Wikimedia Commons as part of a project by the Metropolitan Museum of Art. See the Image and Data Resources Open Access Policy, CC0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=65099463

If I were to rewrite this article today, I would do a better job of integrating the distinction between failure demand and value demand, as described by John Seddon in his Vanguard method.