Stopping the clock is a pernicious practice

There is a tradition among certain service providers to “stop the clock” when measuring process cycle time. They consider that any process activity under the responsibility of someone other than the service provider should not count against the agreed service level. There are two main cases: when the provider is waiting for customer feedback and when the provider is waiting for a third party supplier.

From the point of view of the customer, such practices are pernicious and demonstrate a fundamental misunderstanding of the difference between accountability and responsibility. We may readily agree that a third party might be responsible for any action that might have been escalated to it. But this does not relieve the service provider of its accountability to the customer for the results! And it hardly makes any difference if the service provider has managed to hornswoggle the customer into agreeing to such practices.

Measuring waiting time

If the exclusion of such period from the agreed lead time is, at best, a misleading idea, measuring the amount of time that you are waiting for something to happen is a magnificent idea. This is precisely because you are accountable for delivering results and the more you spend time waiting, the more you prolong the lead time to value.

Indeed, when organizing truly measure how much time they spend waiting, as opposed to performing valuable activities, they are astonished by the results. 90% waiting time is not at all unusual. Really good organizations may have reduced total waiting time to 30-40%. These figures may sound unbelievable; just try to measure objectively how your own organization works. This shocking statistic is one of the key arguments underpinning the use of Kanban to achieve a lean approach to doing work.

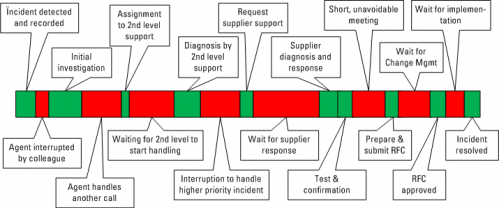

Objective measurement is one of the issues faced in managing waiting as a type of waste. You will probably not get very objective measures if you simply ask people what they do and how long they take doing it. Furthermore, the overhead of making such measures on a regular basis is prohibitive. But, if the measurements are made, the result might look like the timeline in Fig. 1.

Strategies for improving productivity

Given the difficulties in measuring, why should we bother? The reason, of course, is that reducing waiting time is the simplest, least costly and most effective way of reducing lead time and increasing productivity.

More resources?

If mean waiting time is reduced from 90% to 50%, we gain 40% in productivity. How else could we make such gains? We could hire a lot more people and equip them, but this is a very expensive approach that most organizations cannot afford. In fact, productivity almost never increases in proportion to the size of the staff. Some project analysts have even shown that hiring more people when you are late in a project is a sure way of finishing even later!

Streamlined processes?

Another approach is to streamline the process in use. Aside from the fact that this is easier said than done, there is also a risk of lowering the quality of the output if you eliminate the wrong steps. But, if a process could be made more lean and optimized, by all means do it. A good example of such a process improvement is to design the acceptance tests for the output of the work before the work itself is done.

Automation?

A third approach is to automate the performance of work. Since computers will always do work much faster than people can, automation is a good approach—so long as the work can truly be automated. Using a workflow tool to automate informing people of when there is work to do is a good example of largely useless automation, from the perspective of reducing waiting time. A good example would be automating the approval process so that the business rules are implemented in software, rather than having to wait for people to analyze and decide (or even decide without the analysis). Such solutions are obviously appropriate, but only if the work can be simplified so that even a computer can understand it. Be that as it may, there remains a vast realm of knowledge work where full automation is not likely in the near future.

Waiting time measurement techniques

As mentioned above, knowledge workers are not likely to give very precise information about precisely when they start and stop productive work on a given work item. Some organizations have tools in place that act as a sort of stopwatch for measuring time, often linked to a project task. I am seen such tools in production, but I have never seen them used in a consistent and reliable way. Perhaps, however, this form of tracking has become reliable in certain organizations, in which case they might provide useful data.

Otherwise, the best approach is for a third party to shadow the people doing the work and track the amount of time they take, just like the efficiency experts of old. Given the high cost and invasiveness of such an approach, it should only be used to sample data for producing baselines. An annual sampling might be appropriate; perhaps more frequently at the start of a major change initiative.

The size of the sample may require some tuning at first. It will depend on the total volume of process cycles, on the degree of variation within the process and the capability of the organization to deliver results in a predictable way.

The waiting time is generally expressed as a flow efficiency metric, or the percentage of time spent in working (the lead time minus the waiting time) during the calendar time of the process cycle (the lead time). For example, if a process starts at 8:00 and ends at 18:00 the same day, and the total waiting time during that period is 8 hours, then the flow efficiency is 20% (10 hrs – 8 hrs / 10 hrs * 100%).

Reducing waiting time with Kanban

Kanban provides a simple, easy-to-adopt approach to reducing waiting time. It is based on the following principles:

- Work should be broken down into smallish, manageable chunks

- Work in progress by any single person or team should be strictly limited

- Work should be pulled from the upstream activity only when there is downstream capacity to handle it.

Following these principles greatly reduces context switching in work, leading to higher quality work and vastly improved mean lead times.

The diagrams in this posting are licensed to you under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license.

The diagrams in this posting are licensed to you under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license.

Leave a Reply