It has become a commonplace that the throughput of a team’s or individual’s work is significantly slowed by context switching. If, instead of trying to multi-task and performing many different tasks within a given lapse of time, we finish a task before we start another, there will be much less context switching. Consequently, we would be able to complete more work more quickly.

However, there are many types of context switching. Do they all have the same impact on work throughput? Can we measure the different types of context switching? Should we attempt to manage the different types of context switching? Can we do more to manage context switching than just limiting work in progress? Let’s investigate these questions.

The purpose of this discussion is not to provide definitive answers to such questions. Instead, I would like to sketch out the issues involved, put on the table the usefulness of additional research and indicate probably fruitful areas for additional work in finding ways to managed context switching.

Five Types of Context Switching

I have identified five types of context switching:

- Starting a new task after having completed a different task (Old-Finished-New)

- Choosing to work on a different task before having completed the current task, due to a blockage in the current task (Old-Blocked-New)

- Choosing to work on a different task before having completed the current task due to a wandering mind (Old-Wandering-New). Mind wandering may be intentional or unintentional.

- Being obliged by another party to stop working on one task and to start working on another (Old-Preempted-New)

- Taking a pause while working on a task and returning to that task after the pause (Old-Paused-Old)

It is possible that some events combine characteristics of two or more of these types.

When the scientific literature discusses context switching, it does so in terms of interruption and disruption of work. Nonetheless, these scientific articles and the problem of managing the flow of work are concerned with the same issues of the cost of interruption, cognitive impact and the emotional impact of interruption on workers. The typologies I have found in the scientific literature are based on principles such as the following (the references are to the items in the bibliography at the end of this article):

- [a] “Interruptions during the course of the workday might be of the same context as the current task at-hand or they might be random, related to other topics”

- [c] “Immediate, negotiated, mediated, and scheduled”

- [f] There is evidently a difference between an expected interruption and an unexpected interruption. We not only perform better when we expect the interruption; we can only learn to improve performance following interruptions

- [g] External interruptions are those that stem from events in the environment, such as a phone ringing, a colleague entering one’s cubicle, or an email signal. Internal interruptions are those in which one stops a task of her or his own volition.

Differences among the Types of Context Switching

Preparing for Resumption of the Task

When you switch contexts, do you prepare for the resumption of your work when you finally return to the current task? How well do you prepare that resumption? For the type Old-Finished-New, this is not an issue. In the case of Old-Blocked-New, it is possible to determine in advance what will trigger the resumption of the old task and what the next steps will be.

However, when context is switched due to an involuntary wandering mind, the lack of focus and aforethought make it difficult to plan the resumption of work. This case resembles that of someone dozing off while attempting to read. When you regain consciousness you realize that you have lost your place in the text. You end up rereading the same text, sometimes over and over again. This is an extremely inefficient—and frustrating—way of reading. So it is with context switching. When you ultimately return to the old task, you might have only a vague idea of where you were when you left it. You end up redoing some of the same work.

Similarly, when context is switched due to preemption, you might not have the time or the presence of mind to think through how to resume the interrupted task. This depends largely on the pressure to start work on the new task, which is often the case when the new task involves resolving a major incident.

The final case, Old-Paused-Old involves context switching but might, in fact, result in more efficient and effective work. As the brain does its work and becomes depleted of glucose it becomes less effective. Planning a pause to allow for replenishment, especially when that pause does not wait until mental exhaustion, might be better than bravely soldiering on.

Nested tasks

In the description above, you might get the impression that one returns to the interrupted task once the interruption has ended. Instead, it is fully possible that interruptions be nested and re-nested, like the tales in The Three Princes of Serendip. The impact of such recursive context switching is the increased difficulty of returning to earlier contexts.1

According to one study [h], 41% of tasks are not resumed right away after an interruption. Another study [g] reported 23% of interrupted work not being resumed on the same day. The same study reported that being responsible for work increases the likelihood that it will be resumed quickly.

The hypothesis is that the more intervening tasks there are between the moment work on a task is suspended and the moment of returning to that task, the harder it will be to resume that initial task. This hypothesis sounds very reasonable and studies cite workers expressing exactly this opinion. I have found no objective evidence to support it, though. A study of the possible impact of preparing for the resumption of a task during its suspension might elucidate this issue.

Benefits of Context Switching

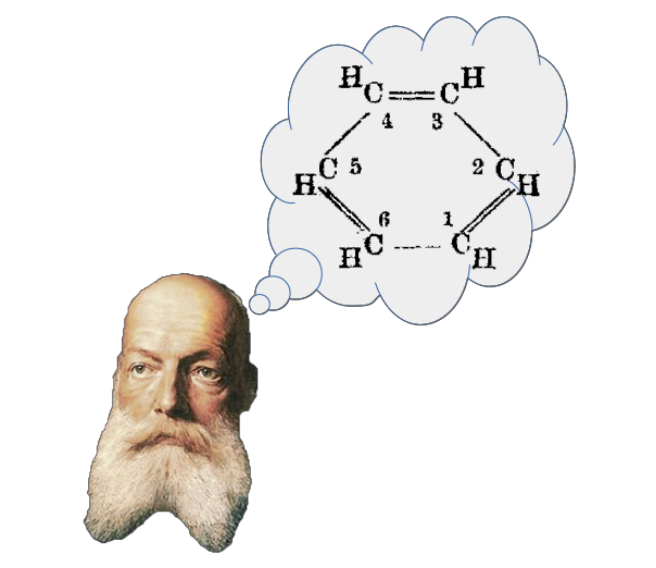

Some authorities believe that context switching may have benefits. The hypothesis is that the serendipitous juxtaposition of two unrelated tasks might provide some inspiration to the worker to solve some problems or complete work more effectively or efficiently. While this is obviously possible—indeed, the literature is replete with examples of such fortuitous inspiration—I have seen no detailed analysis of the frequency of such benefits. In fact, many of the cases provided are not so much the result of context switching as the result of unconscious thought. I might mention Kekulé’s discovery of the benzene ring; Ramanujan’s proofs presented to him by a deity during his dreams; Poincaré’s formulation of his theory of Fuchsian functions; and many other examples.

I would be surprised if it occurred more frequently than a tiny fraction of the cases. Furthermore, even though mind wandering can be deliberate, the potential inspiration cannot be summoned up on demand. Thus, the use of context switching for such benefits is likely to be insignificant.2

In one study, a distinction is made between external task interruption (an event external to the worker causes interruption to the task in hand) and internal interruption (the worker interrupts the task without any evident external reason). Internal interruptions are viewed as generally beneficial whereas external interruptions are detrimental. This view is based on self-reporting from the workers.

In another study, the context of the interruption is understood as a determining factor. When a worker is interrupted by an event that concerns the same topic as the current task, it is considered as beneficial. Events that concern different spheres of work are considered as detrimental. Again, this largely intuitive assumption is based on the subjective self-reporting by the workers.

In short, we may deliberately suspend work on a task, especially when we feel exhausted by the subject matter or realize that further work on the task at the current moment is not likely to be fruitful. Thus, deliberate context switching of the type Old-Paused-Old is generally perceived as being beneficial.

Inevitability of the Context Switch

Old-Finished-New

This type of context switch is both inevitable and desirable. It represents the normal flow of work through a value stream.

Old-Blocked-New

There are two types of reactions to blocked work:

- “Since I cannot advance on this task, I might as well start work on some other task”

- “Since I cannot advance on this task, let’s mobilize the necessary resources to unblock the task”

The former case might seem, in some cases, to be inevitable. However, it represents a situation susceptible to improvement steps designed to avoid such situations. A classic example of such potential for improvement is blockage due to a lack of resource liquidity. To continue with your work, you need input from a person or some resource which, unfortunately, is not immediately available. When that resource is habitually a bottleneck, various improvement steps should be taken to relieve the bottleneck. Given the high degree of variability in work, especially in knowledge work, the existence of such bottlenecks is inevitable. In spite of this inevitability, continual improvement efforts should be undertaken to reduce the impact of such bottlenecks.

The latter case—trying to unblock a task—is the preferred reaction, whenever feasible. Of course, the performance of unblocking actions also represents a context switch. Indeed, there is a second context switch when the unblocking actions are completed and the normal work on the task is resumed.

Old-Wandering-New

There is something of the Walter Mitty in all of us. Whether our wandering minds fantasize about becoming the boss, or reliving issues from home or at work, or having salacious thoughts about colleagues, it is hardly possible to keep focused on our work 100% of the time.

There are positive and negative aspects to the wandering mind. For some, wandering thoughts are part of the creative process. A bit of wandering could be especially beneficial when seeking new solutions to problems. On the other hand, as our mind wanders in unexpected directions, we are likely to arrive at dead ends. Unless such thoughts are part of a relaxation process (see below) they contribute to neither the effectiveness nor the efficiency of our work.

Many factors might affect the propensity to wander, as well as the ease with which we regain focus on our work. Intoxicating substances may facilitate or promote wandering. One study has related age to the process: younger adults wandered more readily, but also regained focus more quickly. A low or depressed mood may lead to greater wandering. Inadequate sleep resulting in high levels of adenosine in the brain may provoke wandering. This may be related to incoherence between the circadian rhythm and the sleep cycle (such as due to jet lag). Furthermore, dull, repetitive and mind-numbing tasks are more likely to lead to wandering than do challenging and novel tasks. One might expect that hopelessly complicated or impossible tasks might lead to more wandering, but I have not found evidence for this one way or the other.

We may wonder if personality traits, especially Openness to Experience and Conscientiousness, may contribute to the propensity to wander.3 In spite of the attractiveness of this hypothesis, models of personality traits have limited explanatory power, given that they are based on biased self-reporting. While those personality types are commonly observed, they have no generally accepted underlying physiological or neurological explanation. Thus, while one might suppose that a highly conscientious person would be less apt to wander, scientific evidence to confirm this hypothesis is lacking. Or, the person might be characterized as conscientious because he or she sticks to the task and does not wander. Similarly, while one might suppose that the active imagination characterizing openness to experience would imply more mental wandering, again, I have seen no evidence to support this.

Analyses of mind wandering and related constructs focus on cases where individuals are solely responsible for tasks. What about the cases where people work together, such as in pair programming? While I have not found any studies of this type of case, intuition tells me that your mind is less likely to wander if you have to synchronize your thoughts and actions with another person. This intuition is supported by studies that showed that more frequent external stimuli decreases the propensity to mind wandering (summarized in [k] p. 949). These external stimuli would correspond to the interactions between the collaborators.

There are practices (again summarized in [k]) by individuals working alone that may also influence the frequency of mind wandering. One practice is verbal shadowing of actions (doing and saying what you are doing). This practice acts like the added stimuli mentioned above, thereby decreasing wandering. While verbal shadowing might sound like a moronic practice of talking to oneself, think of the cinematic coroner who states out loud what she or he is in the progress of seeing in the corpus delicti. On the other hand, insofar as practice makes a given task more automatic, so does mind wandering during that well-rehearsed task increase.

In resumé, is this type of context switch inevitable? There is reason to believe that a very large portion of our thoughts (from 25%-50%!) are not concerned with the tasks with which we are currently concerned. Can we influence the degree to which our minds wander? In all probability we can, by:

- matching tasks to people with appropriate skills

- avoiding having people perform repetitive, mind-numbing work

- making work a more social, multi-person activity.

Old-Preempted-New

Preemption of work is inevitable. It is not economical to maintain a reserve of people and resources capable of immediately handling whatever unexpected and urgent tasks might arise. However, as with blockages, each preemption is also the occasion to ask what could have been done to avoid it. To give a simple example, preventive maintenance is a common way of avoiding the urgent handling of incidents. And yet, many organizations believe that they have neither the time nor the resources to perform such maintenance. The irony is that they make the time to resolve the resulting incidents that could have been avoided, but they do not make the time to prevent those incidents.

Old-Paused-Old

If we pause work with the intention of returning to the same task after the pause, we have the chance to choose when to start the pause and to prepare the return to work. This preparation could be as simple as thinking, “I’ll do that bit after my pause.” The stage is set and the mind is prepared for the return to work. More formal and structured preparation is also possible.

Such pauses are inevi­table insofar as the end of the working day does not always correspond with the end of a task. But one can also expect a certain number of pauses during the working day, pauses that are as desirable as they are inevitable. The alternative to such pauses is the unsustainable, manic dedication to non-stop work. For most of us, this is an impossibility. Our brains and our muscles require pauses to replenish their energy stores and to relieve undo stress. Thus, the judicious use of pauses results in work that is more effective and efficient.

Context Switching Metrics

Whenever we speak of managing the flow of work, the important metrics remain the overall lead times and the cost of providing services, given an acceptable level of risk. These metrics must never be sacrificed in favor of a more detailed metric of more limited scope. However, those more detailed metrics can give insight into how a team works and what might be done to improve the flow of its work.

There are two principal mid-level metrics related to context switching:

- How long does it take to shut down work on the current task (suspension in the discussion below)

- Once you return to the current task, how long does it take to return to the level of performance at which you had been working before the context switch (resumption in the discussion below)

One might be tempted to measure the duration of interruption between context switches. However, this duration is independent of the context switch itself. That being said, there is likely to be a relationship between the duration of the interruption and the ease with which the old task is resumed. A further domain for research would be the degree to which the expected duration of the interruption influences the probability of interrupting. In other words, is a worker more likely to switch to another task if the expected duration of that task is short?

These metrics imply a further metric, namely, the instantaneous level of performance. Since such a metric is essentially impossible to measure, we might replace it with an average level of performance, once the workers have gotten up to speed. We might call this the “cruising velocity” (see Fig. 10).

Let’s look at the life-cycle of work on a task that has been interrupted.

- Planning

During this phase, some form of planning may take place regarding how the task is to be performed. Required tools may be assembled. Responsibilities may be assigned. Note, however, that some people jump right into work with little or no explicit planning. - Acceleration

The work on the task starts, but not all the concepts and details of the approach are yet in place. There might be a number of false starts. However, progress towards achieving the final output of the task accelerates. Do not assume that the acceleration is either smooth or continuous. - Cruising

Work achieves a sustained level of progress. Workers may even enter a state of flow. During cruising velocity there may well be a variety of ups and downs in the progress of the task, but some mean velocity may be calculated, as a basis for comparison of the effect of the context switch. - Interruption

A signal is received that interrupts work, or one that indicates that work should be interrupted. That signal might be the recognition of a blockage, a message calling for preemption of the work or a decision to take a pause. In the case of mind wandering, no explicit signal is received, although some authorities accept the idea that mind wandering can be triggered voluntarily. - Suspension

Depending on the nature of the interruption, there may be a period during which the current task is suspended, pending its resumption at a later time. Suspension might be very orderly, such as when the working day ends, documents are filed, data is saved, applications are closed, perhaps note is made of progress and even plans for how to resume the work the next day. Under some circumstances, there may be no suspension at all, the workers leaving off their tasks, like residents of a village trying to scurry away when being overwhelmed by a volcanic eruption or a tsunami. - Secondary task

Execution starts on the secondary task or a pause starts. This continues until a signal arrives that it is time to return to the initial task. The secondary task may also be interrupted by a tertiary task, and so forth in a recursive way. - Resumption

Resumption of the task resembles the start of another cycle, going back to step 1. However, instead of planning the work from scratch, resumption is a question of recalling where work was left off, remembering the issues being handled, retrieving the information necessary to continue work. Some replanning might also occur. Resumption of work may have been carefully planned during the previous suspension phase. It is more likely, though, that only a minimum of preparation for resumption was made. Resumption often depends on remembering the context of the work to be resumed. Further study of the frequency of types of preparation for resumption and their impact on overall performance is desirable. - Completion

After resumption, the cycle of steps 2-7 continues until the conditions for completion of the task are met. Completion, then, is not a type of work, but rather a status of work. I assume that the conditions for completion can vary widely, so there is little benefit in going into further details here.

The Cost of Context Switching

The blogosphere endlessly repeats the assertion that work is interrupted on average every 11 minutes and that it takes on average 25 minutes to become productive again after the interruption. These blogs generally refer to an article published in the The New York Times [f], which may be downloaded from many places. The Times article refers to a different article published in the Wall Street Journal, which is no longer visible on line. The WSJ article presumably referred, directly or not, to the publication of the original research [g]. What does that original article really say.

First of all, the 11 minute average segment of work includes both segments that are interrupted and segments that are completed. For example, if you resolve an incident or complete a telephone call or write an email (all without interruption) all those types of activities are included in scope of the 11 minute average.

The unit of work being measured is the “working sphere”, a collection of segments of work on a related subject. For example, if you analyze the causes of an incident by reviewing a log and then a colleague telephones you to provide a complement of information about that log, those are two segments of work in the same working sphere (i.e., resolution of that incident). In that case, the interruption of the telephone call is not included in the 11 minute average. If you then switch to the creation of a capacity plan, you have changed to a different working sphere, thus it is a example of an interruption according to the analysis under discussion.

I quote from the original article (p. 324):

The average length of time that the informants spent in central and peripheral working spheres was 11 min. 4 sec., (sd=18 min. 9 sec.) before switching to another working sphere or being interrupted.4,5

Thus, the 11 minutes measures interruptions, the normal completion of a task and the voluntary switch of context to another task.

Note the very wide standard deviation of this measurement (18 min. 9 sec.) as compared to the mean value. No analysis was made of the modality of the measurements. We don’t know if the distribution is normal or if that mean value is a statistic behind which hides a reality of various distinct modes of interruption. Think of the statistician who drowned while crossing a river that averaged 1 meter in depth.

As for the 25 min. duration, many quoters of this study make it seem as if the worker returns immediately to the interrupted task and then struggles for 25 minutes before getting back in the groove (what I call the resumption activity). This is not at all what the research reported. Instead, it says that the 25 minutes may well include multiple segments within other working spheres (p. 326):

before resuming work, our informants worked in an average of 2.26 (sd=2.79) working spheres

So, in fact, the analysis is really only covering the duration of what I call the “secondary task.” There are no measurements of how long it takes to become productive again once the interrupted task is resumed, corresponding to my resumption activity. This remains an open question and may be a fruitful area for additional measurement and analysis.

With this description of the task life-cycle in mind, let us examine more closely how we might measure each type of context switch.

Old-Finished-New

Imagine that work is managed with the help of a kanban board. When the work on the old task is completed, the corresponding card is updated with the end time and moved to the completed column. There is no suspension activity to be measured.

We may include the effort to assess the tasks in the Ready column and choose the next text as part of the Planning activity. The start of Planning may be indicated by the start time indicated on the selected kanban card.

There may be some time between the end of one task and the start of the next text. For a given worker, this may be measured as the difference between the end time of the old task and the start time of the new task. That lapse of time, a form of interruption, could be due to a pause or to a preempting task.

Old-Blocked-New

From the moment when a worker recognizes that a task is blocked until the moment when the unblocking activity starts is theoretically measurable. If flow is well managed, there should hardly be any time between the two events. It makes little sense to try to measure this lapse of time (unless you are studying the neurological bases for the flow of work).

It might make more sense to try to detect and manage problems of dragging one’s heals in unblocking tasks via debriefing exercises. Managers or coaches should be debriefing workers periodically, trying to get coherent accounts of how work is progressing and what is done to unblock work. Improvements might then be suggested and their follow-through tracked.

Old-Wandering-New

Various techniques have been used to measure the propensity for the mind to wander while engaged in intellectual activity. They have been summarized in this article. However, these techniques are hardly feasible for direct measurement of the cost of context switching in a live environment.

There are so many factors that might influence the propensity of the mind to wander that extrapolation from laboratory studies to the live environment enters treacherous ground.

Old-Preempted-New

The nature of preemption mitigates against being able to measure the suspension activity. There is often too much pressure, too much urgency to undertake such measurements. Indeed, the suspension activity itself is likely to suffer when work is preempted, if it is performed at all.

Similarly, the resumption activity is not likely to be measured in the field. However, the results of some laboratory studies indicate that interruptions may have little impact on end-to-end performance. It is assumed that the test subjects compensate for the interruption by working faster afterwards, or by adapting their work habits to take into account the probable interruptions.

We should avoid generalizing from these studies. In spite of their describing some of the tasks as “complex”, they are nonetheless short, simple tasks that require no specialized skills. There are no unknowns to be sought in these tasks, no problems to solve before being able to complete the tasks. The differences in length and complexity of tasks might explain the difference between this micro-analysis in the laboratory and the macro-analysis observable in the field, where interruptions do indeed slow down work.

While it might be feasible to ask workers to report on the time spent on suspension activities, there are three issues with this measurement method:

- Unless the data are gathered immediately after the suspension itself, those data are likely to suffer from self-reporting bias, filtered by memory

- Even if the data were reported immediately after the fact, in urgent situations such reporting would be disruptive and undesirable

- It would be difficult to take into account the Hawthorne effect, according to which the workers would likely change their behavior because they know they are being measured.

Old-Paused-Old

We may distinguish between cases where a pause is predictable in advance, such as a pause for a meal or a pause at the end of the working day, and the cases where the worker pauses on an ad hoc basis. In the former case, it would be easy to ask the worker to report on the duration of the suspension and the resumption activities. The difficulty is that the mere fact of asking for such reports is likely to influence the execution of the tasks, making them more conscientious and longer than might otherwise be the case.

Reporting on suspension activities before an ad hoc pause is likely to be more difficult to obtain. The worker might suddenly decide, “I need a break” and close the mind to further work-related thoughts or simply leave the workplace for a little stroll, a visit to the water cooler or the hot beverage machine. In such cases, suspension is less likely to occur and harder to measure.

Forms of bias in reporting, similar to those for the Old-Preempted-New case, would also have to be taken into account.

Discussion

- Personality Type: Are there personality types that better contribute to improved flow, or is analyzing personality type and flow just a case of circular reasoning?

- Paired Workers: Does working closely with colleagues on the same tasks reduce the number of interruptions to work? If so, is the increase in resource allocation economically justified?

- Cognitive Challenge of Tasks: How does the level of cognition required to perform a task affect the number of interruptions and the overall lead times? Can we assume that the level should not be too low (task should be automated) and should not be too high (task is hopelessly complicated), but just right?

- Nested Interruptions: If interruptions are inevitable, is this also true for nested interruptions? Are there strategies for reducing nesting?

![]() The article Managing Context Switching by Robert S. Falkowitz, including all its contents, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

The article Managing Context Switching by Robert S. Falkowitz, including all its contents, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Bibliography:

[a] Mark, Gloria, Daniela Gudith and Ulrich Klocke (2008), “The Cost of Interrupted Work: More Speed and Stress“, CHI ’08 Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems 107-110.

[b] Adamczyk, Piotr D. and Brian P. Bailey, “If Not Now, When? The Effects of Interruption at Different Moments within Task Execution” CHI ’04 Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 271-278.

[c] McFarlane, D.C. (2002), “Comparison of Four Primary Methods for coordinating the interruption of people in human-computer interaction” Human-Computer Interaction 17 (1),63-139.

[d] “Window of Opportunity: Using the interruption lag to manage disruption in complex tasks” HFES ’02.

[e] Gillier, Tony and Donald Broadbent (1989) “What makes interruptions disruptive? A study of length, similarity and complexity” Psychological Research 50 243-250.

[f] Sullivan, Bob and Hugh Thompson (1989) “Brain, Interrupted” New York Times May 3 2013.

[g] Mark, Gloria, Victor M. Gonzalez and Justin Harris [2005], “No Task Left Behind? Examining the Nature of Fragmented Work“, CHI ’05 Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems 321-330.

[h] O’Connail, B and D. Frohlich (1995) “Timespace in the workplace: dealing with interruptions” Proceedings of CHI, Extended abstracts 262-263.

[i] Salleh, Norsalemah, Emilia Mendes, John Grundy and Giles St. J Burch “An Empirical Study of the Effects of Conscientiousness in Pair Programming using the Five -Factor Personality Model” (2005) Downloaded on 2018.08.27 from https://www.cs.auckland.ac.nz/~john-g/papers/icse2010.pdf.

[j] Axelrod, Vadim, Geraint Rees, Michal Lavidor, and Moshe Bar “Increasing propensity to mind-wander with transcranial direct current stimulation” PNAS March 17, 2015. 112 (11) 3314-3319.

[k] Smallwood J, Schooler JW (2006) “The restless mind“, Psychol Bull 132(6):946–958.

[l] McVay JC, Kane MJ (2010) “Does mind wandering reflect executive function or executive failure? Comment on Smallwood and Schooler (2006) and Watkins (2008)“, Psychol Bull 136(2):188–197, discussion 198–207.

[m] Mooneyham, Benjamin and Jonathan Schooler (2013), “The Costs and Benefits of Mind-Wandering: A Review“, Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology · March 2013, Vol. 67, No. 1, 11–18.

Notes:

1 Although somewhat off-topic, the question of what influences the propensity to return to a task, or even to start a task, is now getting the attention of researchers. Recent work, summarized in an article published by the BBC, refers to the correlation between brain structures and the propensity to procrastinate.

2 I refer explicitly to wandering minds, not dreaming while asleep, which apparently has a known role in problem solving.

3 See Robertson IH, Manly T, Andrade J, Baddeley BT, Yiend J. Oops: “Performance correlates of everyday attentional failures in traumatic brain injured and normal subjects”. Neuropsychologia. 1997;35:747–75

4 The study cited in [i] looks at the opposite question: “What is the impact of Conscientiousness on Pair Programming”. It has the extremely narrow focus of measuring that impact in terms of academic success. I am more interested in the question of whether working closely with others increases conscientiousness, independently of whatever personality types might be involved.

5 In an interview with Gloria Mark she is quoted as saying there is an average of about 3 minutes between interruption or change in activity. She does not make it perfectly clear if she is talking about the same case study, but I think she is talking about changes in segments, not working spheres.

Credits:

Photo of Albert Einstein by Orren Jack Turner, Princeton, N.J. Modified with Photoshop by PM_Poon and later by Dantadd. – This image is available from the United States Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs division under the digital ID cph.3b46036.

Unless otherwise indicated here, the diagrams are the work of the author.

Fig. 4: Portrait by Heinrich von Angeli – Bildindex der Kunst und Architektur: object 02530151 – image file ng1904_067a.jpg, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=429302. Original drawing of the benzene ring by Friedrich August Kekulé von Stradonitz (1829–1896) – Kekule_-_Ueber_einige_Condensationsproducte_des_Aldehyds.pdf, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=11198902

Fig. 5: Images in public domain.

Fig. 6: Downloaded from https://uselectionatlas.org/FORUM/index.php?topic=254584.25

Fig. 7: Downloaded from https://eu.courier-journal.com/story/news/politics/ky-legislature/2017/11/05/jeff-hoover-resigns-house-speaker-over-sexual-harassment-cover-up/833385001/

Dear Mr. Falkowitz,

I must state that you have a great ability of structuring and organizing complicated matters. I understand that context switching is a part of a study how the human brain works. I am sure that it will be an enigma for quite a while. As computers are nothing but calculus machines, the brain can thing apstract. The brain can work with true, untrue or intuitive assotiations. For instance, I would never have learned German if I did not know Croatian. Somthing what seems easy for the human brain is a imposible nightmare for a programmer.

I agree that context switching can be both productive and unproductive. I remember as I was studying at the university, a soluton for a math exercise would come in a period of dosing off or after an event that has nothing to do with the exercise. Somthing would click in the brain and suddenly the solution becomes vivid and obvious.

I would say that context switching has a social context, depending on how we work in teams, as well as an individual, psychological context.

I just came across your articles while looking for content on Agile Service Management. As I am very much looking into Kanban, Scrum,… lately, context switching is a term that comes up regularly. To be honest, this is the deepest and most thorough knowledge I have found on it. I am a bit blown away by it. So thank you!

I believe you should get in touch with Francis Laleman. Your way of writing and deeply capturing the knowledge reminds me very much of him. I am pretty sure the two of you could have some great conversations 🙂