In a recent interview, Thomas Zurbuchen, NASA’s associate administrator for its Science Mission Directorate, said, “The probability of finding extinct life on Mars? That’s the most interesting question.” (Le Temps, 5 August 2017, quote translated from the French article). But how might we know that we have found formerly living beings?

Discovering the remains of a human

Imagine the following. A civilization goes exploring in space and finds—on an otherwise dead planet—a tolerably well preserved human being. How would that civilization know that it has found the remains of a life-form?

This question might be simple to answer if the body were discovered by other homo sapiens. We do recognize our own and we homo sapiens have a strong bias favoring the belief that we are alive.

But suppose the discovering civilization was composed of beings based on entirely different biological processes and structures.

In short, they have never before seen anything like that body, nor any analogous life-form.

What are some of the methods that might be used to identify the body as a dead creature, as opposed to some accidental planetary formation? There is probably no single criterion, no touchstone that can provide an answer. Rather, a combination of factors is likely to be indicative, even if proof might be impossible. Here are some questions that might be asked.

How does the body relate to its surroundings? Is it demarcated from the surrounding material by some discontinuities? We need to have a good idea of extent and limits of the body if we are to be able to analyze its characteristics.

What is the body’s scale relative to the creatures performing the analysis? If the body were millions of times larger or smaller, it might not be recognized as a body. These first two questions relate to the issue of what scope of a system can be considered as alive. Is a DNA molecule alive? A virus? How about a planet, such as Earth?

How complex is the structure of the body? Is it composed of identifiable sub-structures, themselves of a certain level of complexity? Can the body be distinguished, for example, from a mineral crystal? Crystals might be orderly and distinct from the matrix in which they are embedded, but are they ever alive?

Is there reason to believe that the body was a component in a sustainable eco-system, even if that eco-system is itself dead? For example, if you find a dead jellyfish floating in the ocean with the remains of partially digested fish inside and the same fish swimming around it, you have clear evidence that the jellyfish could eat, a key characteristic of life. But if you find that same jellyfish in the middle of a desert, you might wonder if such a structure could have ever survived in such a place. Of course, a waterspout might have picked it up and somehow deposited it elsewhere, but such hypotheses render the conclusion many orders of magnitude less likely. But, what if we discover traces of water frozen underground and fish skeletons near the jellyfish. Now we have traces of an ancient eco-system, making the supposition of life less fantastic. This same approach is used when coprolites are related to the dinosaurs that presumably produced them.

However we define life, a creature must have a means of absorbing and using energy. Do the structures of the body support a hypothesis for how that energy might have been used in a way different from a simple physical process? For example, the action of sunlight on a puddle might result in its evaporation, but we would hardly call the puddle alive. Suppose, though, we find a canteen containing one liquid near one opening of canal that traverses the creature’s body, and the remains of another liquid, with a different chemical composition, near the other opening of that canal. Might not this be evidence of complex processing of the ingested liquid?

Has the surrounding of the body been disturbed or transformed in a way that natural processes could not easily explain? Even the simplest organisms with which we are familiar affect their environment. An unusual distribution of bacteria might be the result of the presence of penicillium. Our paleontologist might find a series of holes in the ground near the body. Are they randomly distributed, perhaps due to karstic erosion, or are they equally spaced in a circle, suggesting that the body had built a shelter, now long disappeared? Can we confuse the pyramidal mountains whose form is due to the natural splitting of rock or the erosion from wind-borne particles, with the structures built in Egypt by the pharaohs over 4’000 years ago?

Is it possible to reanimate the body? A few jolts of lightning, à la Frankenstein, and we see for ourselves that the body, once alive, has come to life again. Alas, what about those molecules in the primordial soup, also struck by lightning? If this indeed was the origin of life on Earth, then (re-)animation is not, by itself, a definitive indicator of life.

Discovering the remains of a robot

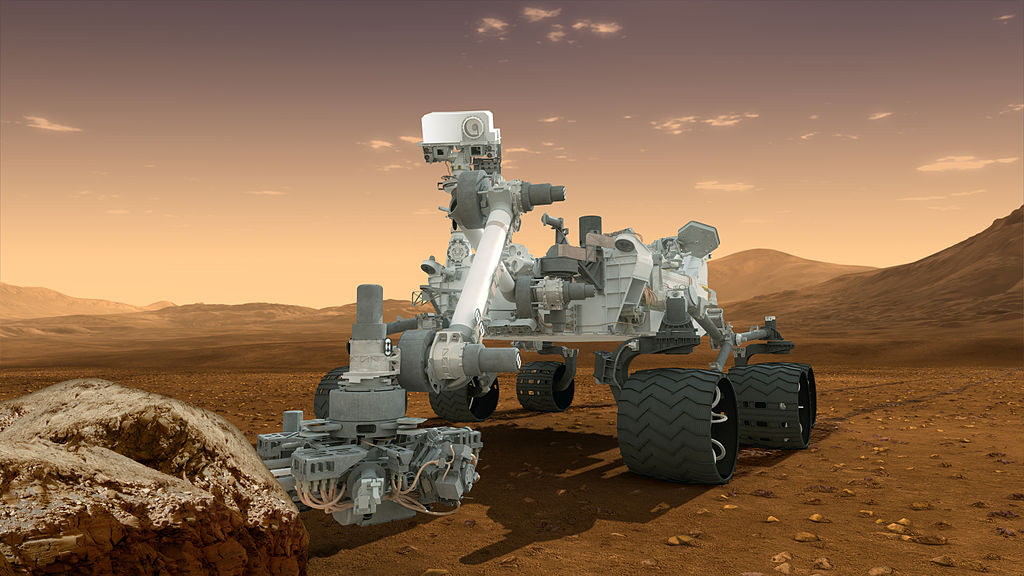

Now, let’s set aside these musings about the discovered human body. Suppose that same civilization has discovered a robot sent to some planet for various scientific purposes. The robot itself no longer functions. Can we apply the same criteria to analyzing that robot as we have done above to analyzing the defunct homo sapiens? What indicators might allow our intrepid analysts to distinguish between a dead human and a dysfunctional robot? What would allow them to say that the one was formerly alive, the other not?

Let us assume that our hypothetical civilization has no experience with either humans or with the robots that humans create. So they cannot simply recognize them based on previous experience. Both are entirely out of their ken.

If anything, a robot is more easily distinguished from its surroundings than a dead body, unless, of course, its plastic components have started to decompose and its metal components subject to rust. Is that so different from the holes eaten in skin by insects?

Robots and humans are roughly on the same scale of size. Size and scale would not be a distinguishing factor.

Robots and humans are both very complex, and this is true at both the macroscopic and microscopic levels. Are the DNA and RNA of our cells any more complex and unexpected than the transistors of a robot’s memory and processors?

How about the relationship of the body to the eco-system? If anything, the robot has got the human beat by a mile. While humans are adaptable to many different eco-systems it seems that they are only really optimized for savannas. But the robot was purpose-built and extremely well adapted to the eco-system in which it is found. In a sense, it obviously belongs where it was found.

I assume that any civilization able to find our robot would also be able to recognize its system for capturing light, converting it to electrical energy, storing and using energy. This relatively complex process, based on multiple specialized structures, is very different from the evaporation of our hypothetical puddle. But how different is it from a human’s digestive system?

Since our robot was created for the precise purpose of disturbing its environment, drilling holes in the ground, picking up dust and pebbles, analyzing chemical composition and physical properties, that impact should be identifiable. And the tire tracks, if still visible, would be just as good evidence as the human’s ancient footsteps, that we are truly dealing with a living entity capable of independent motion.

Reanimating a robot might be as simple as providing new energy, as was the case for Stanley Kubrick’s long dormant robot. Or perhaps some circuits would need to be reattached or joints lubricated. Today, we are not very knowledgeable about what makes humans alive. Many would attribute human life to spiritual or supernatural causes. Would our hypothetical civilization have the same difficulties in comparing the two cases?

Can we distinguish the remains of sophisticated technology from the remains of living creatures?

Would our disinterested investigator be able to distinguish between the corpse and the broken robot, as evidence of a former living creature? Would it be able to conclude that the one was alive, the other not?

One distinction might be the probability that the body was formed as a result of natural processes as opposed to being shaped by some intelligence using technology. Suppose the robot’s exterior were formed from smooth, rolled stainless steel. Could such forms exist in nature? Before we jump to the conclusion that this would be a definitive differentiator, think of some of the beautiful organic forms shaped on the basis of simple mathematical principles, such as a sunflower, the shell of a snail or a diatom.

And even if it were accepted that the robot had to have been manufactured, created by the hand of a creator, does this necessarily imply that the robot was not alive?

Was this alive? vs. Could life have been supported?

Answering the question, “Was this ever alive?” is very different from answering the question, “Could this place have supported life as we know it?” When humans finally do land on Mars, they might find it relatively easy to determine if life, similar to what we know on Earth, ever existing there (excluding, of course, the inevitable terrestrial contamination). Identifying the remains of a completely different life form is a very different issue. I only hope our hypothetical civilization does not have to analyze a human corpse wrapped in an artificial exoskeleton, or a dead policeman brought back to life by replacing 90% of his body with artificial parts.

![]() The article Ancient Life on Mars, by Robert S. Falkowitz, including all its contents, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. This article was also published on LinkedIn.

The article Ancient Life on Mars, by Robert S. Falkowitz, including all its contents, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. This article was also published on LinkedIn.

Credits:

Fig. 1: By NASA/JPL-Caltech [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 2: By Nationalmuseet, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=48076830

Fig. 3: By Morio – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=29969316

Fig. 4: By George Swann – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1152452

A similar question, but relative to life on Earth in the pre-Cambrian period, is usefully discussed here: https://aeon.co/essays/the-shape-of-life-before-the-dinosaurs-on-a-strange-planet