Are the 5 S applicable to service management?

What could the 5 S, originating in the management of the workplace in a factory, mean for service management? The 5 S are generally represented in English as Sort, Systematic Arrangement, Shine, Standardize and Sustain. These terms are derived from the Japanese Seiri ( 整理 ); Seiton ( 整頓 ); Seisou ( 清掃 ); Seiketsu ( 清潔 ) ; and Shitsuke ( 躾 ). Each of these practices is applicable to any form of knowledge work, as well as to service management. Let’s see how.

Seiri

Seiri concerns the sorting of items at the workplace and the removal of all unnecessary items. Knowledge workers will immediately recognize this as the systematic archiving or simple deletion of documents, messages and other information that is no longer pertinent for work. Is your mailbox cluttered with messages that you keep “just in case”, but never really consulted? Do your file systems contain the same file in three different places, or older versions that have no use? In short, are you a pack-rat?

Fig. 1: Keeping the workplace clean

Perhaps the most relevant application of this concept to service management is in the area of knowledge management. Information that is useful as knowledge today, will almost certainly become outdated in the near future. How often do you clean up what is old and irrelevant?

Seiri is also present in the tools we use and our approach to structuring data. Rather than defining useful categories for such records as incidents or changes, we tend instead to rely on full-text indexing. This means that every search for information requires considerable shifting through a lot of chaff, in the hopes of finding the right nugget of information. See also seiton on this point. Furthermore, we often accumulate tons of categories recorded in elaborate taxonomies, most of which remain either unused or used incorrectly. The useful categories are often hard to find and we waste time looking for them.

Seiton

Having eliminating from your workplace unnecessary items, seiton refers to the orderly arrangement of the items you do need. Such arrangements help eliminate various forms of waste, such as the waste of excess movement to find the right tool or the right material, or the waste associated with the extra time spent in finding what you need.

Seiton is thus clearly related to the orderly arrangement of information that any knowledge worker uses as input to his or her work. I return to the point made above about structuring information as a way of making each useful data item, text, knowledge item, etc., quickly accessible.

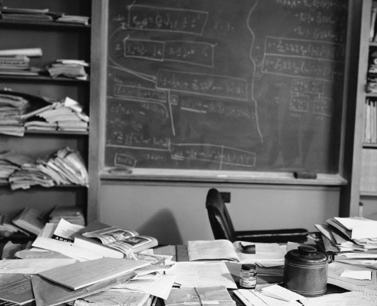

The orderly arrangement of the workplace might be a sensitive item for many knowledge workers, who seem to thrive in what appears to others as a chaotic mess. The worst thing that can happen to such people is when a well-meaning person “cleans up” their workplace for them. Of course, nothing can be found once “order” is established. As any archæologist could tell you, artifacts are arranged as the result of a series of processes. Thus, orderliness can be manifested in the work habits that generate and position documents, as well as in the Cartesian coordinates of those artifacts.

In service management, the particular nuance about seiton is that information about services is normally shared. It is shared between providers and customers; it is shared suppliers and providers; it is shared among colleagues working on the same subject. What is orderly for one person might be chaotic and impenetrable to another. Thus, the order imposed on information, such as incident classifications or configuration categories, must be a shared mental image of order.

Seisou

Seisou concerns keeping the workplace and its tools clean, making it an agreeable place in which to work. The tools of the knowledge worker are generally software applications and we can only hope that the creators of those applications attempt to keep them maintainable, well architected and bug-free. But more appropriate to the knowledge worker is, of course, the cleanliness of the data that is being created and manipulated all day. We all know the mantra, garbage in—garbage out.

In a service management context, the cleanliness of the information we record has a direct impact on the subsequent usefulness of that information and on the waste that poorly

recorded information can engender. A first line of support agent may record information about an incident in an incomprehensible, telescopic way, causing the second line of second line of support to redo work already done. A second line of support person may record little or useless information about how they diagnosed and resolved an incident, making the job of the problem manager who tries to understand the causes of that incident that much the more tedious and lengthy. The work habit of seisou, together with a shared understanding of why clean information is helpful, are more effective than simply making misused fields mandatory.

A second aspect of seisou is using the act of cleaning as the occasion to inspect and maintain. Not only do we ensure that our tools and our workspace is clean, we ensure that our tools are in proper working order. This form of assurance may range from checking event logs to pursuing apparent anomalies in the tools we use, making sure that they are corrected, rather than simply ignoring them and sweeping them under the rug.

Seiketsu

Most workers have an intuitive understanding of the benefits of standardization of work procedures, of seiketsu. Yet, in knowledge work, as in physical labor, there are limits to what is desirable to standardize. Those limits are shaped by the degree of variation in the inputs to the work and the outputs desired. A laborer assembling highly standardized components into a highly standardized output assembly will standardize extensively the approach to doing the assembly. A wood carver needs to adapt the work to the characteristics of the piece of wood being carved, adjusting the work for changes in grain, color, knotholes, wormholes, et. al. And yet, the techniques of designing, carving, burnishing and sanding remain similar from piece to piece.

The same is true in knowledge work. Some forms might be very highly standardized, such as in accounting. Other forms of work, best handled using adaptive case management, are nonetheless approached using standardized patterns. A detective investigating a murder will readily agree that each case is different. But certain methods or work patterns, such as the collection and handling of evidence, is highly standardized.

So it is in service management. Seiketsu is highly applicable in fulfilling the standard service requests. At the other extreme is problem management, where each problem is very different. But within problem management, we can profitably use standardized approaches to work, such as brainstorming structured by a cause and effect diagram, or the five whys technique.

When an organization uses multiple different tools and creates multiple data stores for the same type of data or information, there is also a case for standardization. We should take this with a grain of salt, however. One argument in favor of diversity is that it might encourage innovation or, at the very least, easy adaptation. Having a single, immutable standard tool or database structure that is next to impossible to change is probably just as bad as having multiple tools, making it impossible to compare performance from tool to tool.

Shitsuke

What could shitsuke or “sustain”, “keep in working order” mean in the context of knowledge work and service management? On the one hand, it is obvious that the technology we use to deliver and manage services must be maintained.

The tools we use to support the management of services do require various forms of maintenance, ranging from database reindexing and log purging to version upgrades and patching. But this is not really knowledge work.

On the other hand, sustaining and keeping in working order an organization that does knowledge work, an organization that delivers and manages services, also concerns maintaining good relationships among workers, keeping everyone’s attention focused on the mission of the organization and its vision, and maintaining the levels of motivation and energy that often flag and require periodic renewal. Shitsuke also includes the training and other skills development that is critical to our constantly evolving service systems.

So, the five Ss, developed originally in a manufacturing context, are meaningful and useful in a knowledge work and service management context. We should not be surprised by this, given how many other lean management techniques, such as kanban, also bring very important benefits to service management.

![]()

Photo credits: Fig. 1: licensed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, downloaded from wikiMedia Commons. Figs. 2 & 5: Photo by Robert S. Falkowitz licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Fig. 3: Photo in the public domain, download from Wikimedia Commons. Fig. 4: Photo from the website of the President of the Russian Federation (www.kremlin.ru), licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License Licence.

Perhaps

Good mapping and effort.

I don’t know why but reading this post reminds me of the method David Allen described in his book “Getting things done”.

Do you think his method can help with implementing some of these? 🙂

You raise a good question, Hung: how do you get people to use the 5 S practices? The answer to that question is probably closely related to the general question of how to motivate people to improve.

David Allen’s approach, which I do not know well at all, seems to be more a method for managing the flow of work.

I see, and your comment reminds me of your other article, where you proposed a Continual improvement Maturity model. And yes, getting people to improve is the most important, as per my understanding and experience working with them.

Several did and saw the benefit of improvement and kept doing, but one or two did not regardless of what I tried. Then one or two of the former left to join better companies, while the later seem stay the same forever 😀

GTD is a time management technique, trying to get our minds “clean” of things need to do (and note them down elsewhere). As I just recall I now know my don’t know above, in its own sense GTD works on some of the 5S, such as Sort and Arrangement, and maybe more.