O why why why why why?

Ohno Taiichi provides an oft-quoted example of using the five whys to perform root cause analysis. His neat little scenario of making durable improvements in the operation of an industrial machine gives a misleading view of the reality of understanding the causes of problems. An analysis of the sinking of the Sewol sheds more light on what really happens to cause problems.

A black day in Korea

In April 2014, the Korean ferry Sewol sank while transporting its load of passengers and cargo. 304 of those passengers died as a result, making it what the New York Times called “one of the worst peacetime disasters in the nation’s history.” The remainder of this analysis is based on information provided in the Times.

Issues of design and control

The ferry itself had an unstable design. It had been renovated to add a luxurious art gallery and cabins in the top level, making it top heavy. In fact, the renovation did not follow the approved design, adding 100 tons more than what was approved. Although an inspector was assigned to the renovation to ensure the seaworthiness of the ferry, it appears that a critical “incline test” was not performed. Presumably, this test would have been failed. There is further evidence that Coast Guard personnel, who should have intervened and preventing the sailing of the vessel, were treated to various favors by the ferry company and turned a blind eye to the obvious problems.

Operational Issues

On the fateful day, the ferry loaded twice as much cargo as it was approved to take. This was not an exceptional practice. It had been reported before by the longshoremen, who were be cheated out of their wages. They are paid per ton of loaded cargo, based on the ship’s manifest. But the manifest regularly reported much less cargo than the reality.

There was so much cargo loaded that it was impossible to tie down properly. In addition, the extra cargo caused the ferry to lie too low in the water. Not a problem for the ever resourceful ferry company, a large amount of the ballast water, normally needed to ensure the stability of the vessel, was drained away. As a result, the ferry did not lye too low in the water, an obvious indicator of being overloaded. A shipping association, funded by the shipping companies themselves, is supposed to check that ships are not overloaded with cargo and prevent them from leaving port in an unsafe condition. This check was not performed or, perhaps, the load line painted on the side of the ship was put in a misleading position, masking the overloading.

The Sewol had a regular captain, familiar with the vagaries of the ship and how to avoid problems. But this captain was not aboard that day. A maneuver was performed that the captain had previously indicated was not safe, causing the ship to tilt dangerously. The cargo, much of which was not tied down, started to slide to one side of the ship, exacerbating the situation. The ship started to sink.

There was still hope for the passengers, even though the ship sank much more quickly than might have been expected, had it a proper design and proper operations. However, the crew told the passengers to stay inside when they should have been organizing the evacuation. When questioned about this, the surviving crew members admitted that they had no idea what to do. It later came out that the shipping company had spent a grand total of the equivalent of $2 on safety training during the previous year.

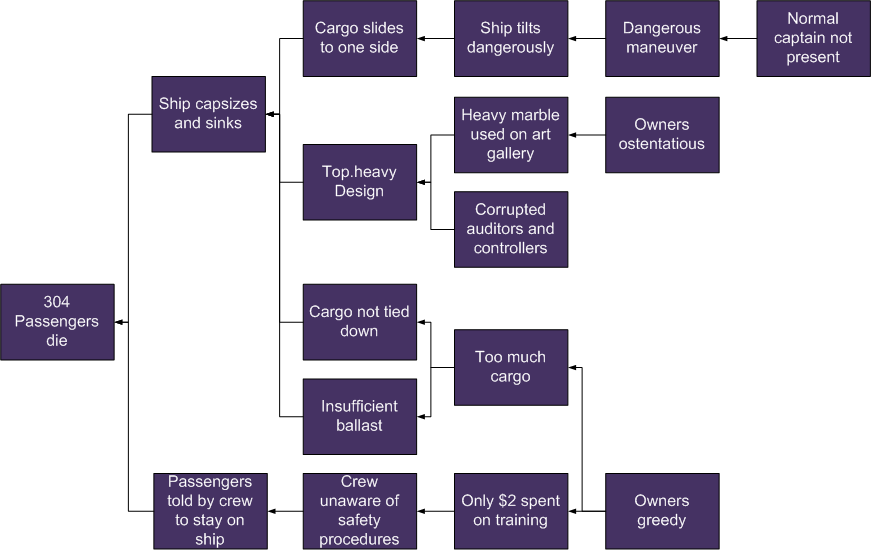

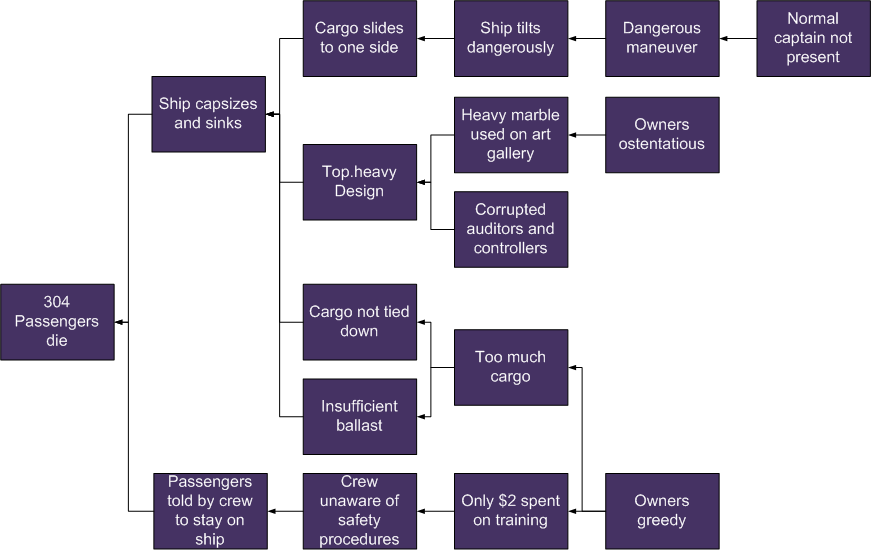

A diagrammatic analysis of the causes and the effects that led to the death of 304 passengers may be found in Fig. 1. The purpose of this diagram is not to be an exhaustive analysis, but rather to show the relations among the various causes and effects.

No single “root cause”

It should be clear that the loss of life due to the incident was not due to any single “root cause.” Rather, it was due to a highly improbable series of contributory conditions and events. Even though the ferry sank, the passengers could have abandoned ship safely, had the crew known what to do. Even though the ferry was unstable, a captain familiar with its condition could have avoided dangerous maneuvers. Even though the ship had a top-heavy design, it could have been much more stable had the ballast not been drained or the cargo overloaded. And even though the cargo was overloaded, had it been tied down, perhaps the dangerous maneuver could have been survived without leading to the sinking.

The same issues for IT

Information technology, like a ship, is a complex socio-technical system. Although some IT services might fail due to simple causes, such as unreliable components, many IT incidents are due to similar series of events, combining exceptional user practices with poorly thought out architectures, unrecognized or unpatched software bugs and exceptional operational conditions, such as redundant equipment shut down for maintenance. Poor user training, ineffective controls built into applications, maintenance done without consideration of risks, lack of technical experience by system administrators, over-reliance on ineffective controls, software that goes unpatched for long periods, no systematic reviews of available patches, lack of resilience and scalability in technical architectures, absence of personnel who have no backups – the list of what could go wrong goes on and on. But only when two, three, four or more situations combine, do those fatal incidents occur.

We need to stop thinking in terms of one-to-one relations between problems and root causes and start thinking more in terms of contributing, multiple factors.

The diagrams in this posting are licensed to you under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license.

The diagrams in this posting are licensed to you under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license.

[…] See, for example, my discussion of causality in The Sinking of the Sewol and Root Cause Analysis2 I had exactly this problem with a company with which I worked. No matter how many times I […]